Chicago River

41°53′11″N 87°38′15″W / 41.88639°N 87.63750°W

| Chicago River | |

|---|---|

Chicago River at night in August 2015 | |

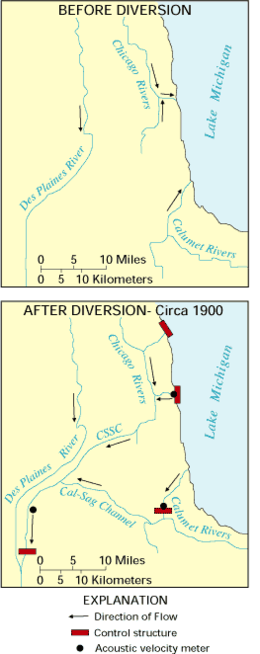

Map of river and flow directions, before and after re-engineering flow via the canal system. Note the "Before" does not show the existing Illinois and Michigan Canal (built 1848), which generally did not affect flow direction. | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| City | Chicago |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Lake Michigan |

| Length | 156 mi (251 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | Chicago River → South Branch → Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal → Des Plaines River → Illinois River → Mississippi River → Gulf of Mexico |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | South Fork Chicago River |

| • right | North Branch Chicago River |

| |

The Chicago River is a system of rivers and canals with a combined length of 156 miles (251 km)[1] that runs through the city of Chicago, including its center (the Chicago Loop).[2] Though not especially long, the river is notable because it is one of the reasons for Chicago's geographic importance: the related Chicago Portage is a link between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Basin, and ultimately the Gulf of Mexico.

The river is also noteworthy for its natural and human-engineered history. In 1887, the Illinois General Assembly decided to reverse the flow of the Chicago River through civil engineering by taking water from Lake Michigan and discharging it into the Mississippi River watershed, partly in response to concerns created by an extreme weather event in 1885 that threatened the city's water supply.[3][n 1] In 1889, the state created the Chicago Sanitary District (now the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District) to replace the Illinois and Michigan Canal with the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, a much larger waterway, because the former had become inadequate to serve the city's increasing sewage and commercial navigation needs.[4] Completed by 1900,[5] the project reversed the flow of the main stem and South Branch and altered the flow of the North Branch by using a series of canal locks and pumping stations, increasing the flow from Lake Michigan into the river, causing the river to empty into the new canal instead. In 1999, the system was named a "Civil Engineering Monument of the Millennium" by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).[6]

The river is represented on the Municipal Flag of Chicago by two horizontal blue stripes.[7] Its three branches serve as the inspiration for the Municipal Device,[8][9][10] a three-branched, Y-shaped symbol that is found on many buildings and other structures throughout Chicago.

Course

[edit]When it followed its natural course, the North and South Branches of the Chicago River converged at Wolf Point to form the main stem, which jogged southward from the present course of the river to avoid a baymouth bar, entering Lake Michigan at about the level of present-day Madison Street.[11] Today, the main stem of the Chicago River flows west from Lake Michigan to Wolf Point, where it converges with the North Branch to flow into the South Branch, where the river's course goes south and west to empty in the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal.

North Branch

[edit]

Early settlers named the North Branch of the Chicago River the Guarie River, or Gary's River, after a trader who may have settled the west bank of the river a short distance north of Wolf Point, at what is now Fulton Street.[12][13] The source of the North Branch is in the northern suburbs of Chicago where its three principal tributaries converge. The Skokie River—or East Fork—rises from a flat plain, historically a wetland, near Park City, Illinois to the west of the city of Waukegan.[14] It then flows southward, paralleling the shore of Lake Michigan, through wetlands, the Greenbelt Forest Preserve and a number of golf courses towards Highland Park, Illinois.[15] South of Highland Park the river passes the Chicago Botanic Gardens and through an area of former marshlands known as the Skokie Lagoons. From the west, the Middle Fork arises near Rondout, Illinois and flows southwards through Lake Forest and Highland Park. The two tributaries of the North and Middle forks merge at the Watersmeet Woods forest preserve west of Wilmette. From there the North Branch flows south towards Morton Grove.[16] The third tributary, the West Fork, rises near Mettawa and flows south through Lincolnshire, Bannockburn, Deerfield, and Northbrook, meeting the North Branch at Morton Grove.[17] In recognition of the work of Ralph Frese in promoting canoeing on and conservation of Chicago-area rivers, the forest preserve district of Cook County, Illinois has designated a section of the East Fork and North Branch from Willow Road in Northfield to Dempster Street in Morton Grove the Ralph Frese River Trail.[18][19]

The North Branch continues southwards through Niles, entering the city of Chicago near the intersection of Milwaukee Avenue and Devon Avenue,[20] from where it serves as the boundary of the Forest Glen community area with Norwood Park and Jefferson Park. This stretch of the river meanders in a south-easterly direction, passing through golf courses and forest preserves until it reaches Foster Avenue, where it passes through residential neighborhoods on the north side of the Albany Park community area.[21] In River Park the river meets the North Shore Channel, a canal with water pumped from Lake Michigan (at Wilmette), built between 1907 and 1910 to increase the flow of the North Branch and help flush it into the South Branch and from there to the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal.[3] From the confluence with the North Shore Channel south to Belmont Avenue the North Branch flows through mostly residential neighborhoods in a man-made channel that was dug to straighten and deepen the river, helping it to carry the additional flow from the North Shore Channel.[22]

South of Belmont the North Branch is lined with a mixture of residential developments, retail parks, and industry until it reaches the industrial area known as the Clybourn Corridor.[23] Here it passes beneath the Cortland Street Drawbridge, which was the first 'Chicago-style' fixed-trunnion bascule bridge built in the United States,[24] and is designated as an ASCE Civil Engineering Landmark and a Chicago Landmark.

At North Avenue, south of the North Avenue Bridge, the North Branch divides, the original course of the river makes a curve along the west side of Goose Island, whilst the North Branch Canal cuts off the bend, forming the island. The North Branch Canal—or Ogden's Canal—was completed in 1857, and was originally 50 feet (15 m) wide and 10 feet (3.0 m) deep allowing craft navigating the river to avoid the bend.[25] The 1902 Cherry Avenue Bridge, just south of North Avenue, was constructed to carry the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway onto Goose Island. It is a rare example of an asymmetric bob-tail swing bridge[26] and was designated a Chicago Landmark in 2007.[27] From Goose Island the North Branch continues to flow south east to Wolf Point where it joins the main stem.

Main stem

[edit]

Since the late 19th century, the source of the main stem of the Chicago River is Lake Michigan. Water enters the river through sluice gates at the Chicago River Controlling Works with a small additional flow provided for the passage of boats between the river and Lake Michigan through the Chicago Harbor Lock.[28] The surface level of the river is maintained at 0.5 to 2 feet (0.15 to 0.61 m) below the Chicago City Datum (579.48 feet [176.63 m] above mean sea level) except for when there is excessive storm run-off into the river or when the level of the lake is more than 2 feet below the Chicago City Datum.[29] Acoustic velocity meters at the Columbus Drive Bridge and the T. J. O'Brien lock on the Calumet River monitor the diversion of water from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River basin, which is limited to an average of 3,200 cubic feet (91 m3) per second per year over the 40-year period from 1980 to 2020.[30]

The main stem flows 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west from the controlling works at Lake Michigan;[31] passing beneath the Outer Drive, Columbus Drive, Michigan Avenue, Wabash Avenue, State Street, Dearborn Street, Clark Street, La Salle Street, Wells Street, and Franklin Street bridges en route to its confluence with the North Branch at Wolf Point. At McClurg Court it passes the Centennial Fountain, which was built in 1989 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago; between May and October the fountain sends an arc of water over the river for ten minutes every hour.[32] On the north bank of the river, near the Chicago Landmark Michigan Avenue Bridge, is Pioneer Court, which marks the site of the homestead of Jean Baptiste Point du Sable who is recognized as the founder of Chicago.[33] On the south bank of the river is the site of Fort Dearborn, an army fort, first established in 1803. Notable buildings surrounding this area include the NBC Tower, the Tribune Tower, and the Wrigley Building. The river turns slightly to the south west between Michigan Avenue and State Street, passing the Trump International Hotel and Tower, 35 East Wacker, and 330 North Wabash. Turning west again the river passes Marina City, the Reid, Murdoch & Co. Building, and Merchandise Mart, and 333 Wacker Drive.

Since the early 2000s, the south shore of the main stem has been developed as the Chicago Riverwalk. It provides a linear, lushly landscaped park intended to offer a peaceful escape from the busy Loop and a tourist attraction. Different sections are named Market, Civic, Arcade, and Confluence. The plans reflect ideas first proposed by the Burnham Plan as early as 1909.

South Branch

[edit]

Before reversal, the South Branch generally arose with joining forks in the marshy area called Mud Lake to flow to where it met the North Branch at Wolf Point forming the main branch.[34] Since reversal, the source of the South Branch of the Chicago River is the confluence of the North Branch and main stem at Wolf Point. From here the river flows south passing the Lake Street, Randolph Street, Washington Street, Madison Street, Monroe Street, Adams Street, Jackson Boulevard, Van Buren Street, Ida B. Wells Drive, and Harrison Street bridges before leaving the downtown Loop community area. Notable buildings that line this stretch of the river include the Boeing Company World Headquarters, the Civic Opera House, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, Union Station and Willis Tower.

The river continues southwards past railroad yards and the St. Charles Air Line Bridge. Between Polk and 18th Streets the river originally made a meander to the east; between 1927 and 1929 the river was straightened and moved 1⁄4 mile (0.40 km) west at this point to make room for a railroad terminal.[35] The river turns to the southwest at Ping Tom Memorial Park where it passes under the Chicago Landmark Canal Street railroad bridge. The river turns westward where it is crossed by the Dan Ryan Expressway; these immovable bridges have a clearance of 60 feet (18 m) requiring large ships that pass underneath to have folding masts.[36]

At Ashland Avenue the river widens to form the U.S. Turning Basin, the west bank of which was the starting point of the Illinois and Michigan Canal.[37] Prior to 1983, this was where the US Coast Guard Rules of the Road, Great Lakes ended & Rules of the Road, Western Rivers began. Since 1983, there is just a single Inland Navigational Rules passed by Congressional Act in 1980 (Public Law 96-591). At the basin the river is joined by a tributary, the South Fork of the river, which is commonly given the nickname Bubbly Creek. A bridge used to span the South Fork at this point that was too low for boats to pass meaning that their cargo needed to be unloaded at the bridge, and the neighborhood at its east end became known as Bridgeport.[38] The river continues to the south west, entering the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal at Damen Avenue. The original West Fork of the South Branch, which before 1935[39] led towards Mud Lake and the Chicago Portage, has been filled in; a triangular intrusion into the north bank at Damen Avenue marks the place where it diverged from the course of the canal.[38] From there, the water flows down the canal through the southwest side of Chicago and southwestern suburbs and, in time, into the Des Plaines River between Crest Hill on the west and Lockport on the east, just north of the border between Crest Hill and Joliet, Illinois, eventually reaching the Gulf of Mexico.

Discharge

[edit]The United States Geological Survey monitors water flow at a number of sites in the Chicago River system. Discharge from the North Branch is measured at Grand Avenue; between 2004 and 2010 this averaged 582 cubic feet (16.5 m3) per second.[40] During the winter months as much as 75% of the flow in the North Branch is due to the discharge of treated sewage from the North Side Water Reclamation Plant into the North Shore Channel.[41] Flow on the main stem is measured at Columbus Drive; between 2000 and 2006 this averaged 136 cubic feet (3.9 m3) per second.[42]

History

[edit]Name

[edit]The name Chicago derives from the 17th century French rendering of shikaakwa or chicagou, the Native American name for ramps (Allium tricoccum), a type of edible wild leek, which grew abundantly near the river. The river, and its region, were named after the plant.[43][44][45]

Exploration and settlement

[edit]Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, though probably not the first Europeans to visit the area, are the first recorded to have visited the Chicago River in 1673, when they wrote of their discovery of the geographically vital Chicago Portage.[46] Marquette returned in 1674, camped a few days near the mouth of the river, then moved on to the Chicago River–Des Plaines River portage, where he stayed through the winter of 1674–75. The Fox Wars effectively closed the Chicago area to Europeans in the first part of the 18th century. The first non-native to re-settle in the area may have been a trader named Guillory, who might have had a trading post near Wolf Point on the Chicago River in around 1778.[47] In 1823 a government expedition used the name Gary River (phonetic spelling of Guillory) to refer to the north branch of the Chicago River.

Jean Baptiste Point du Sable is widely regarded as the first permanent resident of Chicago; he built a farm on the northern bank at the mouth of the river in the 1780s.[48] The earliest known record of Pointe du Sable living in Chicago is the diary of Hugh Heward, who made a journey through Illinois in the spring of 1790. Antoine Ouilmette claimed to have arrived in Chicago shortly after this in July 1790.[49]

In 1795, in a then minor part of the Treaty of Greenville, an Indian confederation granted treaty rights to the United States, to a parcel of land at the mouth of the "Chicago River".[n 2][51] This was followed by the 1816 Treaty of St. Louis and Treaty of Chicago, which ceded additional land in the Chicago area.[52] In 1803, Fort Dearborn was constructed on the bank opposite what had been Point du Sable's settlement, on the site of the present-day Michigan Avenue Bridge.[53] Lieutenant James Strode Swearingen, who led the troops from Detroit to Chicago to establish the fort, described the river as being about 30 yards (27 m) wide and upwards of 18 feet (5.5 m) deep at the place where the fort was intended to be built; the riverbanks were 8 feet (2.4 m) high on the south side and 6 feet (1.8 m) on the north.[54]

Early modifications

[edit]

Between 1816 and 1828 soldiers from Fort Dearborn cut channels through the sandbar at the mouth of the river to allow yawls to bring supplies to the fort.[55] These channels rapidly clogged with sand requiring a new one to be cut. On March 2, 1833, $25,000[n 3] was appropriated by Congress for harbor works, and work began in June of that year under the supervision of Major George Bender, the commandant at Fort Dearborn.[55][57] In January 1834 James Allen took over the supervision of this work[58] and, aided by a February storm that breached the sandbar, on July 12, 1834, the harbor works had progressed enough to allow a 100-short-ton (91 t) schooner, the Illinois to sail up the river to Wolf Point and dock at the wharf of Newberry & Dole.[55] The initial entrance through the sandbar was 200 feet (61 m) wide and 3 to 7 feet (0.91 to 2.13 m) deep, flanked by piers 200 feet (61 m) long on the south wall and 700 feet (210 m) long to the north. Allen's work continued, and by October 1837 the still unfinished piers had been extended to 1,850 and 1,200 feet (560 and 370 m) respectively.[59]

In 1848, the Illinois and Michigan canal linked the river to the Illinois River and the Mississippi Valley across the Chicago Portage. This canal was the farthest west, and the last, of a series of United States' government land grant canals. It provided the only water route from New York City to New Orleans through the country's interior and Chicago.[60]

Reversing the flow

[edit]

During the last ice age, the area that became Chicago was covered by Lake Chicago, which drained south into the Mississippi Valley. As the ice and water retreated, a short 12-to-14-foot (3.7 to 4.3 m) ridge was exposed about a mile inland, which generally separated the Great Lakes' watershed from the Mississippi Valley, except in times of heavy precipitation or when winter ice flows prevented drainage.[61] By the time Europeans arrived, the Chicago River flowed sluggishly into Lake Michigan from Chicago's flat plain. As Chicago grew, this allowed sewage and other pollution into the clean-water source for the city, contributing to several public health problems, like typhoid fever.[62] Starting in 1848, much of the Chicago River's flow was also diverted across the Chicago Portage into the Illinois and Michigan Canal.[63] In 1871, the old canal was deepened in an attempt to completely reverse the river's flow but the reversal of the river only lasted one season.[64]

Finally, in 1900, the Sanitary District of Chicago, then headed by William Boldenweck, completely reversed the flow of the main stem and South Branch of the river using a series of canal locks, increasing the river's flow from Lake Michigan and causing it to empty into the newly completed Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. In 1999, this system was named a "Civil Engineering Monument of the Millennium" by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).[6] Before this time, the Chicago River was known by many local residents of Chicago as "the stinking river" because of the massive amounts of sewage and pollution that poured into the river from Chicago's booming industrial economy.[65]

Through the 1980s, the river was quite dirty and often filled with garbage; however, during the 1990s, it underwent extensive cleaning as part of an effort at beautification by Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley.[66]

In 2005, researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign created a three-dimensional, hydrodynamic simulation of the Chicago River, which suggested that density currents are the cause of an observed bi-directional wintertime flow in the river. At the surface, the river flows east to west, away from Lake Michigan, as expected. But deep below, near the riverbed, water seasonally travels west to east, toward the lake.[67]

All outflows from the Great Lakes Basin are regulated by the joint U.S.-Canadian Great Lakes Commission, and the outflow through the Chicago River is set under a U.S. Supreme Court decision (1967, modified 1980 and 1997). The city of Chicago is allowed to remove 3,200 cubic feet per second (91 m3/s) of water from the Great Lakes system; about half of this, 1 billion US gallons per day (44 m3/s), is sent down the Chicago River, while the rest is used for drinking water.[68] In late 2005, the Chicago-based Alliance for the Great Lakes proposed re-separating the Great Lakes and Mississippi River basins to address such ecological concerns as the spread of invasive species.[69]

Eastland disaster

[edit]

In 1915, the SS Eastland, an excursion steam-liner preparing to leave the dock on the south gangway between the Clark Street Bridge and La Salle Street Bridge, rolled over, killing 844 of the more than 2500 passengers. The roll of the heavy steamer happened very quickly and many of the passengers were trapped under water by the hull, moving objects such as pianos and tables, the crush of bodies, or their heavy clothes. Frantic if disordered rescue attempts ensued and early versions of what may be regarded as trauma teams formed to address the shocking scene. The site on the south bank at the southeast end of the La Salle Street Bridge is now the location of a memorial first dedicated in 1989.[70]

Chicago flood of 1992

[edit]On April 13, 1992, a flood occurred when a pile driven into the riverbed caused stress fractures in the wall of a long-abandoned tunnel of the Chicago Tunnel Company near the Kinzie Street railroad bridge. Most of the 60-mile (97 km) network of underground freight railway, which encompasses much of downtown, was eventually flooded, along with the lower levels of buildings it once serviced and attached underground shops and pedestrian ways.

Bridges

[edit]

The first bridge across the Chicago River was constructed over the North Branch near the present day Kinzie Street in 1832. A second bridge, over the South Branch near Randolph Street, was added in 1833.[71] The first moveable bridge was constructed across the main stem at Dearborn Street in 1834.[72] Today, the Chicago River has 38 movable bridges spanning it, down from a peak of 52 bridges.[73] These bridges are of several different types, including trunnion bascule, Scherzer rolling lift, swing bridges, and vertical-lift bridges.

Pollution

[edit]The Chicago River has been highly affected by industrial and residential development with attendant changes to the quality of the water and riverbanks. Several species of freshwater fish are known to inhabit the river, including largemouth and smallmouth bass, rock bass, crappie, bluegill, catfish, and carp. The river also has a large population of crayfish. The South Fork of the Main (South) Branch, which was the primary sewer for the Union Stock Yards and the meat packing industry, was once so polluted that it became known as Bubbly Creek.[74] Illinois has issued advisories regarding eating fish from the river due to PCB and mercury contamination, including a "do not eat" advisory for carp more than 12 inches long.[75] There are concerns that silver carp and bighead carp, now invasive species in the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers, may reach the Great Lakes through the Chicago River.[76] A program on the north channel next to Goose Island seeks to increase wildlife habitat through the use of floating plant islands. The program is managed by the non-profit conservation group Urban Rivers with assistance from the Shedd Aquarium.[77] As with some other bodies of water in the United States, the river has seen several successful efforts to improve water quality since the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972 and related state and local efforts.[78][79]

Recreation

[edit]Despite the pollution concerns, the Chicago River remains a very popular target for freshwater recreational fishing. In 2006, the Chicago Park District started the annual "Mayor Daley's Chicago River Fishing Festival", which has increased in popularity with each year. Between 2013 and 2016, the Chicago Park District opened four boat houses, two on the south branch and two on the north, for river recreation.[80]

Mouth of the river

[edit]-

Near the mouth of the Chicago River 1831

-

Near the mouth of the Chicago River 1838

-

Near the mouth of the Chicago River 1893

-

Near the mouth of the Chicago River c. late 1800s

-

Mouth of the river in the early 20th century

Dyeing the river

[edit]St. Patrick's Day

[edit]

As part of a more than fifty-year-old Chicago tradition, the Chicago River is dyed green in observance of St. Patrick's Day.[81] The actual event occurs on the Saturday on or before March 17.

The tradition of dyeing the river green arose by accident in 1961 when plumbers used fluorescein dye to trace sources of illegal pollution discharges.[82] The dyeing of the river is still sponsored by the local plumbers union.[83] The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) disallowed the use of fluorescein for this purpose, since it was shown to be harmful to the river.[82] The parade committee switched to a mix involving forty pounds of powdered vegetable dye.[84] Though the committee closely guards the exact formula, they insist that it has been tested and verified safe for the environment.[85]

The environmental organization Friends of the Chicago River disapproves of dyeing the river, saying the practice "gives the impression that it is lifeless and artificial", adding "Friends doesn't think that the river should be treated as a decoration for an annual holiday, but treasured and cared for as the wonderful natural and recreational resource it deserves to be".[86]

In 2009 First Lady Michelle Obama, a Chicago native, inspired by the river tradition, requested that the water in the White House fountains be dyed green to celebrate St. Patrick's Day.[87]

Chicago Cubs rally

[edit]For the Chicago Cubs rally and parade for their 2016 World Series Championship celebrations, the river was dyed Cubs blue.[88] Friends of the Chicago River executive director Margaret Frisbie told the Chicago Sun-Times, "We do not want to set a precedent where, every time we want to celebrate, we dye the river a different color and potentially hurt the aquatic life that lives in it. While it may seem festive, it's actually potentially harming a natural resource."[89]

-

The river dyed green for Saint Patrick's Day in 2015

-

The river dyed blue during the Chicago Cubs' 2016 World Series celebration

McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum

[edit]The southwest bridgehouse of the DuSable Bridge (Michigan Avenue) serves as a museum on the river, its history, its challenges, and its renaissance. The McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum is a 5-floor, 1,613-square-foot (149.9 m2) museum that opened on June 10, 2006; it is named for Robert R. McCormick, formerly owner of the Chicago Tribune and president of the Chicago Sanitary District. The Robert R. McCormick Foundation was the major donor that helped meet the $950,000 cost to open the museum. It is run by the Friends of the Chicago River, a non-profit environmental organization. Visitors are also allowed to access the bridge's gear room; during the spring and fall bridge lifting visitors can see the bridge gears in operation as the leaves are raised and lowered. Due to its small size and tight access stairway only 79 people are allowed inside the museum at any one time.[90] In October 2019, Chicago Tribune cultural arts writer Steve Johnson profiled the museum, calling its gear room where the DuSable Bridge mechanics can be viewed "a little chamber of heaven for infrastructure nerds".[91]

Monitoring the impact of extreme weather events on the Chicago District

[edit]The US Army Corps of Engineers have monitored the development of harbors and channels for navigation on the Great Lakes since the early 1800s. They began monitoring hydrological conditions and lake levels in 1918. A December 26, 2012 report revealed that Chicago District navigation infrastructure did receive significant impacts from Hurricane Sandy with some areas experiencing severe shoaling. Chicago Shoreline Project mitigated the damage of the storm event.[5]

The same report noted that the low Great Lakes levels were drought-induced, caused by a very hot, dry summer and a lack of a solid snowpack in the winter of 2012. At the time of the report, December 2012, Lake Michigan-Huron was 28 inches below its long-term average which is near the record lows of 1964.[5] Historic lake levels for Lake Michigan reported from 1918 to 1998 show that the low levels observed in 1964 were the lowest since 1918.[92] In 2012 Lake Michigan-Huron's seasonal rise was about 4 inches where it usually is about 12 inches. Normally the Chicago River water level is two feet lower than the lake and therefore does not flow into the lake. If the lake level falls too low threatening to reverse the river flow, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago would be forced to close locks between the lake and river for longer periods of time, limiting navigation. A reversal flow of the Chicago River into Lake Michigan would have a negative impact on navigation and on the quality of Lake Michigan water, which is the source of drinking water.[5] Chicago's raw sewage in the river is normally carried upstream toward the Mississippi River which flows south towards the Gulf of Mexico. On January 9, 2013, Chicago meteorologists announced 320 days without at least one inch of snowfall. Water levels in the lake started to level off with the river and sewage was visible at the cusp of the locks, just a few hundred feet from Lake Michigan. David St. Pierre, executive director of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago warned the low lake levels were nearing a point of real concern.[93] However, the District maintains that it is not possible for the river to reverse due to low lake level alone.[94][95]

Measurements taken by the US Army Corps in January 2013 revealed that both Lake Michigan and Lake Huron had reached their "lowest ebb since record keeping began in 1918, and the lakes could set additional records over the next few months, the corps said. The lakes were 74 centimetres (29 inches) below their long-term average and had declined 43 centimetres (17 inches) since January 2012".[96]

See also

[edit]- Bubbly Creek

- Centennial Fountain

- Ogden Slip

- Illinois Department of Transportation

- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in Illinois

- List of rivers of Illinois

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "About Friends of the Chicago River". Friends of the Chicago River. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ "Where is the Chicago River?" Archived October 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Friends of the Chicago River. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ a b Hill 2000, pp. 139–151

- ^ Chicago-Based Rail Holding Company Gains Exemption for Northern Lines Railway Control (Report). Vol. 2. ChicagoSalud Inc, State of Illinois. December 2004. p. 4.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d US Army Corps of Engineers (December 26, 2012). How the Chicago District has 'weathered' recent storm events (Report). Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ a b "Chicago Wastewater System". American Society of Civil Engineers. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ^ "Municipal Flag of Chicago". Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "The Chicago Municipal Device (Y-Shaped Figure)". Chicago Public Library. Archived from the original on September 3, 2006. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ "The Municipal Device". Forgotten Chicago. Archived from the original on April 9, 2011. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ "Chicago's municipal device: The city's symbol lurking in plain sight". WBEZ. Archived from the original on September 7, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ Hill 2000, p. 32

- ^ Quaife 1913, p. 138

- ^ Keating, William H. (1824). Narrative of an expedition to the source of St. Peter's river, Lake Winnepeek, Lake of the Woods, &c., performed in the year 1823 (volume 1). H. C. Carey & I. Lea. p. 172. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ Hill 2000, p. 171

- ^ Solzman 2006, pp. 63–64

- ^ Solzman 2006, p. 66

- ^ Solzman 2006, p. 59

- ^ Megan, Graydon (December 12, 2012). "Ralph Frese, 1926-2012". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ^ "Ralph Frese, 1926 – 2012". Forest Preserves of Cook County. Forest Preserve District of Cook County. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ^ Solzman 2006, p. 67

- ^ Solzman 2006, pp. 67–72

- ^ Solzman 2006, p. 72

- ^ Solzman 2006, p. 85

- ^ Hess, Jeffrey A. (1999). "North Avenue Bridge: HAER No. IL-154". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

- ^ Duis 1998, p. 95

- ^ "Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway, Bridge No. Z-2, Spanning North Branch Canal at North Cherry Avenue, Chicago, Cook County, IL". Historic American Engineering Record. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ^ "Chicago Landmarks: Individual Landmarks and Landmark Districts designated as of January 1, 2008" (PDF). Commission on Chicago Landmarks. January 1, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ García, Carlos M.; Oberg, Kevin; García, Marcelo H. (December 2007). "ADCP Measurements of Gravity Currents in the Chicago River, Illinois". Journal of Hydraulic Engineering. 133 (12): 1356–1366. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2007)133:12(1356).

- ^ "Title 33 of the Code of Federal Regulations 207.420". Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ Jaffe, Martin (June 2009). "Water Supply Planning in the Chicago Metropolitan Region" (PDF). Sea Grant Law and Policy Journal. 2 (1): 1–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ "Chicago River & North Shore Channel River Corridors & Wilmette Harbor" (PDF). Illinois Coastal Management. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ A Native's Guide to Chicago. Lake Claremont Press. 2004. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-893121-23-2.

- ^ Baumann, Timothy E. (December 2005). "The Du Sable Grave Project in St. Charles, Missouri". The Missouri Archaeologist. 66: 59–76.

- ^ Husar, John (December 12, 1996). "Maps Unlock River's History". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ "Chicago River Straightening". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Archived from the original on May 7, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ^ Solzman 2006, p. 231

- ^ Solzman 2006, p. 226

- ^ a b Husar, John (December 12, 1996). "Maps Unlock River's History". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ Cahan, Richard; Williams, Michael (2011). The Lost Panoramas: When Chicago Changed its River and the Land Beyond. Cityfiles Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-9785450-7-9.

- ^ "Annual statistics for USGS 05536118 North Branch of Chicago River at Grand Avenue at Chicago, IL". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ Jackson, P. Ryan; Garcia, Carlos M.; Oberg, Kevin A.; Johnson, Kevin K.; Garcia, Marcelo H. (2008). "Density currents in the Chicago River: Characterization, effects on water quality, and potential sources" (PDF). Science of the Total Environment. 401 (1–3): 130–143. Bibcode:2008ScTEn.401..130J. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.04.011. hdl:1912/2250. PMID 18499229. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ "Annual statistics for USGS 05536123 Chicago River at Columbus Drive at Chicago, IL". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on September 5, 2016. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ Durkin Keating, Ann (2005). "Chicago". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ^ Zeldes, Leah A. (April 5, 2010). "Ramping up: Chicago by any other name would smell as sweet". Dining Chicago. Chicago's Restaurant & Entertainment Guide, Inc. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Swenson, John F. (Winter 1991). "Chicago: Meaning of the Name and Location of Pre-1800 European Settlements". Early Chicago. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ Quaife 1913, pp. 22–24

- ^ Meehan, Thomas A (1963). "Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, the First Chicagoan". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 56 (3). Illinois State Historical Society: 439–453. JSTOR 40190620.

- ^ Pacyga, Dominic A. (2009). Chicago: A Biography. University of Chicago Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-226-64431-8.

- ^ Letter from Antoine Ouilmette to John H. Kinzie dated June 1, 1839, reproduced in Blanchard, Rufus (1898). Discovery and Conquests of the Northwest, with the History of Chicago (volume 1). R. Blanchard and Company. p. 574. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ Charles J. Kappler (1904). "Treaty with the Wyandot, Etc., 1795". U.S. Government treaties with American Indian tribes. Oklahoma State University Library. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010. Retrieved August 1, 2009.

- ^ "Fort Dearborn". Encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Archived from the original on December 27, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Treaty with the Ottawa, etc. 1816 Archived September 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Durkin Keating, Ann. "Fort Dearborn". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. p. 477. Archived from the original on December 27, 2011. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ Journal of Lieutenant James Strode Swearingen reproduced in Quaife 1913, pp. 373–377

- ^ a b c Holland, Robert A. (2005). Chicago in Maps. New York: Rizzoli International Publications. pp. 102–109. ISBN 978-0-8478-2743-5.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Andreas 1884, p. 234

- ^ Hill 2000, pp. 69–75

- ^ Andreas 1884, p. 235

- ^ Schroer, Blanche; Peterson, Grant; Bradford, S. Sydney (September 14, 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Illinois and Michigan Canal". National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Killey, Myrna M. 1998. "Illinois' Ice Age Legacy." Illinois State Geological Survey GeoScience Education Series 14.

- ^ "Did 90,000 people die of typhoid fever and cholera in Chicago in 1885?". The Straight Dope. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ Cain, Louis P. "Water". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. p. 1324. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ Miller, Donald L. City of the Century (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996) p. 427

- ^ Grossman, Ron (August 29, 1995). "The Flow of History". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ Wolf, Garret (2012). "A city and its river: an urban political ecology of the Loop and Bridgeport in Chicago" (PDF). Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College: 85–86. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ "The River Under the River". Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering (CEE) at the University of Illinois. Archived from the original on April 25, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ "Lake Michigan Diversion Supreme Court Consent Decree" (PDF). Deq.state.mi.us. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2009. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ "Groups to study separating Great Lakes and Mississippi River basins". The Pantagraph. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ^ Hilton, George W. "Eastland". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. p. 408. Archived from the original on April 23, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ Chicago, 1835 (Map). Albert F. Scharf. 1908.

- ^ Solzman 2006, p. 35

- ^ Solzman 2006, p. 29

- ^ Solzman 2006, p. 25

- ^ "Illinois Fish Advisory: Chicago River". Illinois Department of Public Health. Archived from the original on March 14, 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Stern, Andrew (February 20, 2006). "Scientists Fear Leaping Carp To Invade US Great Lakes". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 18, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ O'Connell, Patrick M. (June 22, 2018). "A 'wild mile' on the Chicago River? It might be closer than you think". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 25, 2018. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ Axelrod, Jim (October 22, 2024). "How cities like Portland and Chicago are breathing new life into their rivers". CBS News. Retrieved October 23, 2024.

- ^ Stone, Chelsey (June 22, 2024). "The Chicago River was a toxic wasteland. Now it's an urban oasis". National Geographic. Retrieved October 23, 2024.

- ^ "Boathouses - Chicago Park District". Archived from the original on September 11, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ "Dyeing of the River". St. Patrick's Day Parade. Saint Patrick's Day Parade Committee of Chicago. 2009. Archived from the original on March 18, 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Battle, British (March 20, 2003). "Other cities dye-ing to know what turns Chicago River green". The Columbia Chronicle. The Fairfield Mirror, via UWIRE. Archived from the original on April 19, 2009.

- ^ "Green Chicago River". Sponsor website. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ^ Lydon, Dan. "The Man Who Dyed the River Green: Stephen M. Bailey". Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ^ O'Carroll, Eoin (March 16, 2009). "Is the dye in the Chicago River really green?". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ "The Impact of Dyeing the River Green". Friends of the Chicago River. March 18, 2015. Archived from the original on December 27, 2019.

- ^ White House fountains flow green for St. Patrick's Day, Mark Silva, March 18, 2009

- ^ staff, Chicago Tribune. "Chicago River is dyed blue for Cubs celebration". Chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Spielman, Fran (November 3, 2016). "Conservationists make waves about dying river Cubbie blue". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on December 27, 2019.

- ^ "McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum". McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019.

- ^ Johnson, Steve (October 8, 2019). "Hurried Chicagoans hate it when the river bridges open. The Chicago River Museum sells tickets". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 13, 2019.

- ^ Chicago River/Lakeshore Area Assessment (PDF) (Report). Vol. 2. Department of Natural Resources, State of Illinois. October 2000. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Continuing Drought Could Lead To Reversal of Chicago River Flow". January 9, 2013. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ "MWRD: Not possible for Chicago River to reverse on its own due to low lake level" (PDF) (Press release). Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago. January 10, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Flannery, Mike (January 9, 2013). "Drought won't affect Chicago River much after all". Chicago News and Weather. FOX 32 News. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ "Lake Huron, Lake Michigan hit lowest water levels on record". Cbc.ca. Associated Press. February 8, 2013. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Andreas, Alfred Theodore (1884). History of Chicago. From the earliest period to the present time (volume 1). Chicago, A. T. Andreas. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- Duis, Perry (1998). Challenging Chicago: Coping With Everyday Life, 1837–1920. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02394-3.

- Hill, Libby (2000). The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History. Chicago: Lake Claremont Press. ISBN 1-893121-02-X.

- Quaife, Milo Milton (1913). Chicago and the Old Northwest, 1673–1835. University of Chicago Press. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- Solzman, David M. (2006). The Chicago River: An Illustrated History and Guide to the River and its Waterways (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-76801-5.

External links

[edit]- Friends of the Chicago River

- GreenChicagoRiver.com

- Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- News

- "Feds order cleanup of Chicago River". Chicago Tribune. Associated Press. May 12, 2011. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2011.