Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin | |

|---|---|

| |

Stalin at the Tehran Conference, 1943 | |

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 3 April 1922 – 16 October 1952[a] | |

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Molotov (as Responsible Secretary) |

| Succeeded by | Nikita Khrushchev (as First Secretary) |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union[b] | |

| In office 6 May 1941 – 5 March 1953 | |

| First Deputy |

|

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Succeeded by | Georgy Malenkov |

| Minister of the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union[c] | |

| In office 19 July 1941 – 3 March 1947 | |

| Premier | Himself |

| Preceded by | Semyon Timoshenko |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Bulganin |

| People's Commissar for Nationalities of the Russian SFSR | |

| In office 8 November 1917 – 7 July 1923 | |

| Premier | Vladimir Lenin |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili 18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1878 Gori, Russian Empire |

| Died | 5 March 1953 (aged 74) Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Resting place |

|

| Political party | |

| Other political affiliations | |

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Alma mater | Tiflis Theological Seminary |

| Awards | Full list |

| Signature |  |

| Nickname | Koba |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Red Army |

| Years of service | 1918–1920 |

| Rank | Generalissimo (from 1945) |

| Commands | Soviet Armed Forces (from 1941) |

| Battles/wars | |

Central institution membership Other offices held

| |

| Leader of the Soviet Union | |

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin[f] (born Dzhugashvili;[g] 18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1878 – 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretary of the Communist Party from 1922 to 1952 and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers from 1941 until his death. Initially governing as part of a collective leadership, Stalin consolidated power to become a dictator by the 1930s. He codified his Leninist interpretation of Marxism as Marxism–Leninism, while the totalitarian political system he established became known as Stalinism.

Born into a poor Georgian family in Gori, Russian Empire, Stalin attended the Tiflis Theological Seminary before joining the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. He raised funds for Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction through robberies, kidnappings and protection rackets, and edited the party's newspaper, Pravda. Repeatedly arrested, he underwent internal exiles to Siberia. After the Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution of 1917, Stalin joined the governing Politburo, and following Lenin's death in 1924, won the struggle to lead the country. Under Stalin, the doctrine of socialism in one country became central to the party's ideology. His five-year plans, launched in 1928, led to agricultural collectivisation and rapid industrialisation, establishing a centralised command economy. Resulting disruptions to food production contributed to a famine in 1932–1933 which killed millions, including in the Holodomor in Ukraine. Between 1936 and 1938, Stalin eradicated his political opponents and those deemed "enemies of the working class" in the Great Purge, after which he had absolute control of the party and government. Under his regime, an estimated 18 million people passed through the Gulag system of forced labour camps, and more than six million were deported to remote regions of the Soviet Union, which together resulted in millions of deaths.

Stalin promoted Marxism–Leninism abroad through the Communist International and supported European anti-fascist movements, including in the Spanish Civil War. In 1939, his government signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany, enabling the Soviet invasion of Poland. Germany broke the pact by invading the Soviet Union in 1941, leading Stalin to join the Allies of World War II. Despite huge losses, the Soviet Red Army repelled the German invasion and captured Berlin in 1945, ending the war in Europe. The Soviet Union, which had annexed the Baltic states and territories from Finland and Romania amid the war, established Soviet-aligned states in Central and Eastern Europe. The Soviet Union and the United States emerged as global superpowers, and entered a period of tension known as the Cold War. Stalin presided over post-war reconstruction and the first Soviet atomic bomb test in 1949. During these years, the country experienced another famine and a state-sponsored antisemitic campaign culminating in the "doctors' plot". In 1953, Stalin died after suffering a stroke, and was succeeded as leader by Georgy Malenkov and later by Nikita Khrushchev, who in 1956 denounced Stalin's rule and initiated a campaign of "de-Stalinisation".

Widely considered one of the 20th century's most significant figures, Stalin was the subject of a pervasive personality cult within the international Marxist–Leninist movement, which revered him as a champion of socialism and the working class. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Stalin has retained a degree of popularity in post-Soviet states as an economic moderniser and victorious wartime leader who cemented the Soviet Union as a major world power. Conversely, his regime has been widely condemned for overseeing mass repressions, ethnic cleansing, and famines which caused the deaths of millions.

Early life

1878–1899: Childhood to young adulthood

Stalin was born on 18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1878[h] in Gori, Georgia,[2] then part of the Tiflis Governorate of the Russian Empire.[3][4] An ethnic Georgian, his birth name was Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili (Russified as Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili).[g] His parents were Besarion Jughashvili and Ekaterine Geladze;[5] Stalin was their third child and the only one to survive past infancy.[6] After Besarion's shoemaking workshop went into decline, the family fell into poverty, and he became an alcoholic who beat his wife and son.[7][8] Ekaterine and her son left the home by 1883 and began wandering, moving through nine different rented rooms over the next decade.[9] In 1888, Stalin enrolled at the Gori Church School[10] in a position secured by a family friend,[11] where he excelled academically.[12] He faced health problems: an 1884 smallpox infection left him with facial scars,[13] and at age 12 he was seriously injured when he was struck by a phaeton, causing a lifelong disability in his left arm.[14]

In 1894, Stalin enrolled as a trainee Russian Orthodox priest at the Tiflis Theological Seminary, enabled by a scholarship.[15] He initially achieved high grades,[16] but lost interest in his studies[17] and was repeatedly confined to a cell for rebellious behaviour.[18] After joining a forbidden book club,[19] Stalin was influenced by Nikolay Chernyshevsky's pro-revolutionary novel What Is To Be Done?[20] Another influential text was Alexander Kazbegi's The Patricide, with Stalin adopting the nickname "Koba" from its bandit protagonist.[21] After reading his Das Kapital, Stalin devoted himself to Karl Marx's philosophy of Marxism,[22] which was on the rise as a variety of socialism opposed to the Tsarist authorities.[23] He began attending secret workers' meetings,[24] and left the seminary in April 1899.[25]

1899–1905: Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

In October 1899, Stalin began working as a meteorologist at the Tiflis observatory.[26] He attracted a group of socialist supporters,[27] and co-organised a secret workers' meeting[28] at which he convinced many to take strike action on May Day 1900.[29] The empire's secret police, the Okhrana, became aware of Stalin's activities and attempted to arrest him in March 1901, but he went into hiding[30] and began living off donations from friends.[31] He helped plan a demonstration in Tiflis on May Day 1901 at which 3,000 marchers clashed with the authorities.[32] In November 1901, Stalin was elected to the Tiflis Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), a Marxist party founded in 1898.[33]

That month, Stalin travelled to Batumi.[34] His militant rhetoric proved divisive among the city's Marxists, some of whom suspected that he was an agent provocateur.[35] Stalin began working at the Rothschild refinery storehouse, where he co-organised two workers' strikes.[36] After the strike leaders were arrested, he co-organised a mass demonstration which led to the storming of the prison.[37] Stalin was arrested in April 1902[38] and sentenced to three years of exile in Siberia, arriving in Novaya Uda in November 1903.[39] After one failed attempt, Stalin escaped from his exile in January 1904 and travelled to Tiflis,[40] where he co-edited the Marxist newspaper Proletariatis Brdzola ("Proletarian Struggle") with Filipp Makharadze.[41] During his exile, the RSDLP had become divided between Vladimir Lenin's "Bolshevik" faction and Julius Martov's "Mensheviks".[42] Stalin, who detested many Mensheviks in Georgia, aligned himself with the Bolsheviks.[43]

1905–1912: Revolution of 1905 and aftermath

In January 1905, government troops massacred protesters in Saint Petersburg and unrest spread across the Empire in the Revolution of 1905.[44] Stalin was in Baku in February when ethnic violence broke out between Armenians and Azeris,[45] and formed Bolshevik "battle squads" which he used to keep the city's warring ethnic factions apart.[46] His armed squads also attacked local police and troops,[47] raided arsenals,[48] and raised funds via protection rackets on large local businesses and mines.[49][50] In November 1905, the Georgian Bolsheviks elected Stalin as one of their delegates to a Bolshevik conference in Tampere, Finland,[51] where he met Lenin for the first time.[52] Although Stalin held Lenin in deep respect, he vocally disagreed with his view that the Bolsheviks should field candidates for the 1906 election to the State Duma; Stalin viewed parliamentary process as a waste of time.[53] In April 1906, Stalin attended the RSDLP's Fourth Congress in Stockholm, where the party—then led by its Menshevik majority—agreed that it would not raise funds using armed robbery.[54] Lenin and Stalin disagreed with this,[55] and privately discussed continuing the robberies for the Bolshevik cause.[56]

Stalin married Kato Svanidze in July 1906,[57] and in March 1907 she gave birth to their son Yakov.[58] Stalin, who by now had established himself as "Georgia's leading Bolshevik",[59] in June 1907 organised the robbery of a bank stagecoach in Tiflis in order to fund the Bolsheviks' activities. His gang ambushed the convoy in Erivansky Square with gunfire and home-made bombs; around 40 people were killed, but all his gang escaped.[60] Stalin settled in Baku with his wife and son,[61] where Mensheviks confronted him about the robbery and voted to expel him from the RSDLP, but he ignored them.[62] Stalin secured Bolshevik domination of Baku's RSDLP branch[63] and edited two Bolshevik newspapers.[64] In November 1907, his wife died of typhus,[65] and he left his son with her family in Tiflis.[66] In Baku he reassembled his gang,[67] which attacked Black Hundreds and raised money through racketeering, counterfeiting, robberies[68] and kidnapping the children of wealthy figures for ransom.[69]

In March 1908, Stalin was arrested and imprisoned in Baku.[70] He led the imprisoned Bolsheviks, organised discussion groups, and ordered the killing of suspected informants.[71] He was sentenced to two years of exile in Solvychegodsk in northern Russia, arriving there in February 1909.[72] In June, Stalin escaped to Saint Petersburg,[73] but was arrested again in March 1910 and sent back to Solvychegodsk.[74] In June 1911, Stalin was given permission to move to Vologda, where he stayed for two months.[75] He then escaped to Saint Petersburg,[76] where he was arrested again in September 1911 and sentenced to a further three years of exile in Vologda.[77]

1912–1917: Rise to the Central Committee and Pravda

In January 1912, the first Bolshevik Central Committee was elected at the Prague Conference.[78] Lenin and Grigory Zinoviev decided to co-opt Stalin to the committee, which Stalin (still in exile in Vologda) agreed to.[78][79] Lenin believed that Stalin, as a Georgian, would help secure support from the empire's minority ethnicities.[80] In February 1912, Stalin again escaped to Saint Petersburg,[81] where he was tasked with converting the Bolshevik weekly newspaper, Zvezda ("Star") into a daily, Pravda ("Truth").[82] The new newspaper was launched in April 1912 and Stalin's role as editor was kept secret.[83] In May 1912, he was again arrested and sentenced to three years of exile in Siberia.[84] In July, he arrived in Narym,[85] where he shared a room with fellow Bolshevik Yakov Sverdlov.[86] After two months, they escaped to Saint Petersburg,[87] where Stalin continued work on Pravda.[88]

After the October 1912 Duma elections, Stalin wrote articles calling for reconciliation between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks; Lenin criticised him[89] and he relented.[90] In January 1913, Stalin travelled to Vienna,[91] where he researched the "national question" of how the Bolsheviks should deal with the Empire's national and ethnic minorities.[92] His article "Marxism and the National Question"[93] was first published in the March, April, and May 1913 issues of the Bolshevik journal Prosveshcheniye[94] under the pseudonym "K. Stalin". The alias, which he had used since 1912, is derived from the Russian for steel (stal), and has been translated as "Man of Steel".[95] In February 1913, Stalin was again arrested in Saint Petersburg[96] and sentenced to four years of exile in Turukhansk in Siberia, where he arrived in August.[97] Still concerned over a potential escape, the authorities moved him to Kureika in March 1914.[98]

1917: Russian Revolution

While Stalin was in exile, Russia entered the First World War, and in October 1916 he and other exiled Bolsheviks were conscripted into the Russian Army.[99] They arrived in Krasnoyarsk in February 1917,[100] where a medical examiner ruled Stalin unfit for service due to his crippled arm.[101] Stalin was required to serve four more months of his exile and successfully requested to serve it in Achinsk.[102] Stalin was in the city when the February Revolution took place; the Tsar abdicated and the Empire became a de facto republic.[103] In a celebratory mood, Stalin travelled by train to Petrograd (as Saint Petersburg had been renamed) in March.[104] He assumed control of Pravda alongside Lev Kamenev,[105] and was appointed as a Bolshevik delegate to the executive committee of the Petrograd Soviet, an influential workers' council.[106]

The existing government of landlords and capitalists must be replaced by a new government, a government of workers and peasants.

The existing pseudo-government which was not elected by the people and which is not accountable to the people must be replaced by a government recognised by the people, elected by representatives of the workers, soldiers and peasants and held accountable to their representatives.

Stalin's editorial in Pravda, October 1917[107]

Stalin helped organise the July Days uprising, an armed display of strength by supporters of the Bolsheviks.[108] After the demonstration was suppressed, the Provisional Government initiated a crackdown on the party, raiding Pravda.[109] Stalin smuggled Lenin out of the paper's office and took charge of his safety, moving him between Petrograd safe houses before smuggling him to nearby Razliv.[110] In Lenin's absence, Stalin continued editing Pravda and served as acting leader of the Bolsheviks, overseeing the party's Sixth Congress.[111] Lenin began calling for the Bolsheviks to seize power by toppling the Provisional Government, a plan which was supported by Stalin and fellow senior Bolshevik Leon Trotsky, but opposed by Kamenev, Zinoviev, and other members.[112]

On 24 October, police raided the Bolshevik newspaper offices, smashing machinery and presses; Stalin salvaged some of the equipment.[113] In the early hours of 25 October, Stalin joined Lenin in a Central Committee meeting in Petrograd's Smolny Institute, from where the Bolshevik coup—the October Revolution—was directed.[114] Bolshevik militia seized Petrograd's power station, main post office, state bank, telephone exchange, and several bridges.[115] A Bolshevik-controlled ship, the Aurora, opened fire on the Winter Palace; the Provisional Government's assembled delegates surrendered and were arrested.[116] Stalin, who had been tasked with briefing the Bolshevik delegates of the Second Congress of Soviets about the situation, had not played a publicly visible role.[117] Trotsky and other later opponents used this as evidence his role had been insignificant, although historians reject this,[118] citing his role as a member of the Central Committee and as an editor of Pravda.[119]

In Lenin's government

1917–1918: People's Commissar for Nationalities

On 26 October 1917, Lenin declared himself chairman of the new government, the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom).[120] Stalin supported Lenin's decision not to form a coalition with the Socialist Revolutionary Party, although a coalition was formed with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries.[121] Stalin became part of an informal leadership group alongside Lenin, Trotsky, and Sverdlov, and his importance within the Bolshevik ranks grew.[122] Stalin's office was near Lenin's in the Smolny Institute,[123] and he and Trotsky had direct access to Lenin without an appointment.[124] Stalin co-signed Lenin's decrees shutting down hostile newspapers,[125] and co-chaired the committee drafting a constitution for the newly-formed Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.[126] He supported Lenin's formation of the Cheka security service and the Red Terror, arguing that state violence was an effective tool for capitalist powers.[127] Unlike some Bolsheviks, Stalin never expressed concern about the Cheka's rapid expansion and the Red Terror.[127]

Having left his role as Pravda editor,[128] Stalin was appointed the People's Commissar for Nationalities.[129] He took Nadezhda Alliluyeva as his secretary,[130] later marrying her in early 1919.[131] In November 1917, he signed the Decree on Nationality, granting ethnic minorities the right to secession and self-determination.[132] He travelled to Helsingfors to meet with the Finnish Social Democrats, and granted Finland's request for independence from Russia in December.[133] Due to the threats posed by the First World War, in March 1918 the government relocated from Petrograd to the Moscow Kremlin.[134] Stalin supported Lenin's desire to sign an armistice with the Central Powers;[135] Stalin thought this necessary because he—unlike Lenin—was unconvinced that Europe was on the verge of proletarian revolution.[136] The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed in March 1918,[137] ceding vast territories and angering many in Russia; the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries withdrew from the coalition government.[138] The Bolsheviks were renamed the Russian Communist Party.[139]

1918–1921: Military command

In May 1918, during the intensifying Russian Civil War, Sovnarkom sent Stalin to Tsaritsyn to take charge of food procurement in Southern Russia.[140] Eager to prove himself as a commander,[141] he took control of regional military operations and befriended Kliment Voroshilov and Semyon Budyonny, who later formed the core of his military support base.[142] Stalin sent large numbers of Red Army troops to battle the region's White armies, resulting in heavy losses and drawing Lenin's concern.[143] In Tsaritsyn, Stalin commanded the local Cheka branch to execute suspected counter-revolutionaries, often without trial,[144] and purged the military and food collection agencies of middle-class specialists, whom were also executed.[145] His use of state violence was at a greater scale than most Bolshevik leaders approved of,[146] for instance, he ordered several villages torched to ensure compliance with his food procurement program.[147]

In December 1918, Stalin was sent to Perm to lead an inquiry into how Alexander Kolchak's White forces had been able to decimate Red troops there.[148] He returned to Moscow between January and March 1919,[149] before being assigned to the Western Front at Petrograd.[150] When the Red Third Regiment defected, he ordered the public execution of captured defectors.[149] In September he returned to the Southern Front.[149] During the war, Stalin proved his worth to the Central Committee by displaying decisiveness and determination.[141] However, he also disregarded orders and repeatedly threatened to resign when affronted.[151] In November 1919, the government awarded him the Order of the Red Banner for his service.[152]

The Bolsheviks won the main phase of the civil war by the end of 1919.[153] By that time, Sovnarkom had turned its attention to spreading proletarian revolution abroad, forming the Communist International in March 1919; Stalin attended its inaugural ceremony.[154] Although Stalin did not share Lenin's belief that Europe's proletariat were on the verge of revolution, he acknowledged that Soviet Russia remained vulnerable.[155] In February 1920, he was appointed to head the Workers' and Peasants' Inspectorate (Rabkrin);[156] that same month he was also transferred to the Caucasian Front.[157]

The Polish–Soviet War broke out in early 1920, with the Poles invading Ukraine,[158] and in May, Stalin was moved to the Southwest Front.[159] Lenin believed that the Polish proletariat would rise up to support an invasion, but Stalin argued that nationalism would lead them to support their government's war effort.[160] Stalin lost the argument and accepted Lenin's decision.[157] On his front, Stalin became determined to conquer Lvov; in focusing on this goal, he disobeyed orders to transfer his troops to assist Mikhail Tukhachevsky's forces at the Battle of Warsaw in early August, which ended in a major defeat for the Red Army.[161] Stalin then returned to Moscow,[162] where Tukhachevsky blamed him for the loss.[163] Humiliated, he demanded demission from the military, which was granted on 1 September.[164] At the 9th Party Congress in late September, Trotsky accused Stalin of "strategic mistakes"[165] and claimed that he had sabotaged the campaign; Lenin joined in the criticism.[166] Stalin felt disgraced and his antipathy toward Trotsky increased.[167]

1921–1924: Lenin's final years

The Soviet government sought to bring neighbouring states under its domination; in February 1921 it invaded the Menshevik-governed Georgia,[168] and in April 1921, Stalin ordered the Red Army into Turkestan to reassert Soviet control.[169] As People's Commissar for Nationalities, Stalin believed that each ethnic group had the right to an "autonomous republic" within the Russian state in which it could oversee various regional affairs.[170] In taking this view, some Marxists accused him of bending too much to bourgeois nationalism, while others accused him of remaining too Russo-centric.[171] In his diverse native Caucasus, however, Stalin opposed the idea of separate autonomous republics, arguing that these would oppress ethnic minorities within their territories; instead, he called for a Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic.[172] The Georgian Communist Party opposed the idea, resulting in the Georgian affair.[173] In mid-1921, Stalin returned to the South Caucasus, calling on Georgian communists to reject the chauvinistic nationalism which he argued had marginalised the Abkhazian, Ossetian, and Adjarian minorities.[174] In March 1921, Nadezhda gave birth to another of Stalin's sons, Vasily.[175]

After the civil war, workers' strikes and peasant uprisings broke out across Russia in opposition to Sovnarkom's food requisitioning project; in response, Lenin introduced market-oriented reforms in the New Economic Policy (NEP).[176] There was also turmoil within the Communist Party, as Trotsky led a faction calling for abolition of trade unions; Lenin opposed this, and Stalin helped rally opposition to Trotsky's position.[177] At the 11th Party Congress in March and April 1922, Lenin nominated Stalin as the party's General Secretary, which was intended as a purely organisational role. Although concerns were expressed that adopting the new position would overstretch his workload and grant him too much power, Stalin was appointed to the post.[178]

Stalin is too crude, and this defect which is entirely acceptable in our milieu and in relationships among us as communists, becomes unacceptable in the position of General Secretary. I therefore propose to comrades that they should devise a means of removing him from this job and should appoint to this job someone else who is distinguished from comrade Stalin in all other respects only by the single superior aspect that he should be more tolerant, more polite and more attentive towards comrades, less capricious, etc.

— Lenin's Testament, 4 January 1923[179]

In May 1922, a massive stroke left Lenin partially paralysed.[180] Residing at his Gorki dacha, his main connection to Sovnarkom was through Stalin.[181] Despite their comradeship, Lenin disliked what he referred to as Stalin's "Asiatic" manner and told his sister Maria that Stalin was "not intelligent".[182] The two men argued on the issue of foreign trade; Lenin believed that the Soviet state should have a monopoly on foreign trade, but Stalin supported Grigori Sokolnikov's view that doing so was impractical.[183] Another disagreement came over the Georgian affair, with Lenin backing the Georgian Central Committee's desire for a Georgian Soviet Republic over Stalin's idea of a Transcaucasian one.[184] They also disagreed on the nature of the Soviet state; Lenin called for establishment of a new federation named the "Union of Soviet Republics of Europe and Asia",[185] while Stalin believed that this would encourage independence sentiment among non-Russians.[186] Lenin accused Stalin of "Great Russian chauvinism", while Stalin accused Lenin of "national liberalism".[187] A compromise was reached in which the federation would be named the "Union of Soviet Socialist Republics" (USSR), whose formation was ratified in December 1922.[185]

Their differences also became personal; Lenin was angered when Stalin was rude to his wife Krupskaya during a telephone conversation.[188] In the final years of his life, Krupskaya provided leading figures with Lenin's Testament, which criticised Stalin's rude manners and excessive power and suggested that he be removed as general secretary.[189] Some historians have questioned whether Lenin wrote the document, suggesting that it was written by Krupskaya;[190] Stalin never publicly voiced concerns about its authenticity.[191] Most historians consider it an accurate reflection of Lenin's views.[192]

Consolidation of power

1924–1928: Succeeding Lenin

Upon Lenin's death in January 1924,[193] Stalin took charge of the funeral and was a pallbearer.[194] To bolster his image as a devoted Leninist amid his growing personality cult, Stalin gave nine lectures at Sverdlov University on the Foundations of Leninism, later published in book form.[195] At the 13th Party Congress in May 1924, Lenin's Testament was read only to the leaders of the provincial delegations.[196] Embarrassed by its contents, Stalin offered his resignation as General Secretary; this act of humility saved him, and he was retained in the post.[197]

As General Secretary, Stalin had a free hand in making appointments to his own staff, and implanted loyalists throughout the party.[198] Favouring new members from proletarian backgrounds to "Old Bolsheviks", who tended to be middle-class university graduates,[199] he ensured that he had loyalists dispersed across the regions.[200] Stalin had much contact with young party functionaries,[201] and the desire for promotion led many to seek his favour.[202] Stalin also developed close relations with key figures in the secret police: Felix Dzerzhinsky, Genrikh Yagoda, and Vyacheslav Menzhinsky.[203] His wife gave birth to a daughter, Svetlana, in February 1926.[204]

In the wake of Lenin's death, a power struggle emerged to become his successor: alongside Stalin was Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Nikolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, and Mikhail Tomsky.[205] Stalin saw Trotsky—whom he personally despised[206]—as the main obstacle to his dominance,[207] and during Lenin's illness had formed an unofficial triumvirate (troika) with Kamanev and Zinoviev against him.[208] Although Zinoviev was concerned about Stalin's growing power, he rallied behind him at the 13th Congress as a counterweight to Trotsky, who now led a faction known as the Left Opposition.[209] Trotsky's supporters believed that the NEP conceded too much to capitalism, and they called Stalin a "rightist" for his support of the policy.[210] Stalin built up a retinue of his supporters within the Central Committee[211] as the Left Opposition were marginalised.[212]

In late 1924, Stalin moved against Kamenev and Zinoviev, removing their supporters from key positions.[213] In 1925, the two moved into open opposition to Stalin and Bukharin[214] and launched an unsuccessful attack on their faction at the 14th Party Congress in December.[215] Stalin accused Kamenev and Zinoviev of reintroducing factionalism, and thus instability.[215] In mid-1926, Kamenev and Zinoviev joined with Trotsky to form the United Opposition against Stalin;[216] in October the two agreed to stop factional activity under threat of expulsion, and later publicly recanted their views.[217] The factionalist arguments continued, with Stalin threatening to resign in October and December 1926, and again in December 1927.[218] In October 1927, Trotsky was removed from the Central Committee;[219] he was later exiled to Kazakhstan in 1928 and deported from the country in 1929.[220]

Stalin was now the supreme leader of the party and state.[221] He entrusted the position of head of government to Vyacheslav Molotov; other important supporters on the Politburo were Voroshilov, Lazar Kaganovich, and Sergo Ordzhonikidze,[222] with Stalin ensuring his allies ran state institutions.[223] His growing influence was reflected in naming of locations after him; in June 1924 the Ukrainian city of Yuzovka became Stalino,[224] and in April 1925, Tsaritsyn was renamed Stalingrad.[225] In 1926, Stalin published On Questions of Leninism,[226] in which he argued for the concept of "socialism in one country", which was presented as an orthodox Leninist perspective despite clashing with established Bolshevik views that socialism could only be achieved globally through the process of world revolution.[226] In 1927, there was some argument in the party over Soviet policy regarding China. Stalin had called for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), led by Mao Zedong, to ally itself with Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang (KMT) nationalists, viewing a CCP-KMT alliance as the best bulwark against Japanese imperial expansionism. Instead, the KMT repressed the CCP and a civil war broke out between the two sides.[227]

1928–1932: First five-year plan

Economic policy

We have fallen behind the advanced countries by fifty to a hundred years. We must close that gap in ten years. Either we do this or we'll be crushed.

This is what our obligations before the workers and peasants of the USSR dictate to us.

— Stalin, February 1931[228]

The Soviet Union lagged far behind the industrial and agricultural development of the Western powers.[229] Stalin's government feared attack from capitalist countries,[230] and many communists, including in Komsomol, OGPU, and the Red Army, were eager to be rid of the NEP and its market-oriented approach.[231] They had concerns about those who profited from the policy: affluent peasants known as "kulaks" and small business owners, or "NEPmen".[232] At this point, Stalin turned against the NEP, which put him on a course to the "left" even of Trotsky or Zinoviev.[233]

In early 1928, Stalin travelled to Novosibirsk, where he alleged that kulaks were hoarding grain and ordered them be arrested and their grain confiscated, with Stalin bringing much of the grain back to Moscow with him in February.[234] At his command, grain procurement squads surfaced across West Siberia and the Urals, with violence breaking out between the squads and the peasantry.[235] Stalin announced that kulaks and the "middle peasants" must be coerced into releasing their harvest.[236] Bukharin and other Central Committee members were angered that they had not been consulted about the measure.[237] In January 1930, the Politburo approved the "liquidation" of the kulak class, which was exiled to other parts of the country or concentration camps.[238][239] By July 1930, over 320,000 households had been affected.[238] According to Dmitri Volkogonov, de-kulakisation was "the first mass terror applied by Stalin in his own country."[240]

In 1929, the Politburo announced the mass collectivisation of agriculture,[242] establishing both kolkhoz collective farms and sovkhoz state farms.[243] Although officially voluntary, many peasants joined the collectives out of fear they would face the fate of the kulaks.[244] By 1932, about 62% of households involved in agriculture were part of collectives, and by 1936 this had risen to 90%.[245] Many collectivised peasants resented the loss of their private farmland,[246] and productivity slumped.[247] Famine broke out in many areas,[248] with the Politburo frequently being forced to dispatch emergency food relief.[249] Armed peasant uprisings broke out in Ukraine, the North Caucasus, Southern Russia, and Central Asia, reaching their apex in March 1930; these were suppressed by the army.[250] Stalin responded with an article insisting that collectivisation was voluntary and blaming violence on local officials.[251] Although he and Stalin had been close for many years,[252] Bukharin expressed concerns and regarded them as a return to Lenin's old "war communism" policy. By mid-1928, he was unable to rally sufficient support in the party to oppose the reforms;[253] in November 1929, Stalin removed him from the Politburo.[254]

Officially, the Soviet Union had replaced the "irrationality" and "wastefulness" of a market economy with a planned economy organised along a long-term and scientific framework; in reality, Soviet economics were based on ad hoc commandments issued often to make short-term targets.[255] In 1928, the first five-year plan was launched by Stalin with a main focus on boosting Soviet heavy industry;[256] it was finished a year ahead of schedule, in 1932.[257] The country underwent a massive economic transformation:[258] new mines were opened, new cities like Magnitogorsk constructed, and work on the White Sea–Baltic Canal began.[258] Millions of peasants moved to the cities, and large debts were accrued purchasing foreign-made machinery.[259]

Many major construction projects, including the White Sea–Baltic Canal and the Moscow Metro, were constructed largely through forced labour.[260] The last elements of workers' control over industry were removed, with factory managers receiving privileges;[261] Stalin defended wage disparity by pointing to Marx's argument that it was necessary during the lower stages of socialism.[262] To promote intensification of labour, medals and awards as well as the Stakhanovite movement were introduced.[241] Stalin argued that socialism was being established in the USSR while capitalism was crumbling during the Great Depression.[263] His rhetoric reflected his utopian vision of the "new Soviet person" rising to unparallelled heights of human development.[264]

Cultural and foreign policy

In 1928, Stalin declared that class war between the proletariat and their enemies would intensify as socialism developed.[265] He warned of a "danger from the right", including from within the Communist Party.[266] The first major show trial in the USSR was the Shakhty Trial of 1928, in which middle-class "industrial specialists" were convicted of sabotage.[267] From 1929 to 1930, show trials were held to intimidate opposition;[268] these included the Industrial Party Trial, Menshevik Trial, and Metro-Vickers Trial.[269] Aware that the ethnic Russian majority may have concerns about being ruled by a Georgian,[270] he promoted ethnic Russians throughout the state bureaucracy and made Russian compulsory in schools, albeit in tandem with local languages.[271] Nationalist sentiment was suppressed.[272] Conservative social policies were promoted to boost population growth; this included a focus on strong family units, re-criminalisation of homosexuality, restrictions on abortion and divorce, and abolition of the Zhenotdel women's department.[273]

Stalin desired a "cultural revolution",[274] entailing both the creation of a culture for the "masses" and the wider dissemination of previously elite culture.[275] He oversaw a proliferation of schools, newspapers, and libraries, as well as advancement of literacy and numeracy.[276] Socialist realism was promoted throughout the arts,[277] while Stalin wooed prominent writers, namely Maxim Gorky, Mikhail Sholokhov, and Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy.[278] He expressed patronage for scientists whose research fit within his preconceived interpretation of Marxism; for instance, he endorsed the research of agrobiologist Trofim Lysenko despite the fact that it was rejected by the majority of Lysenko's scientific peers as pseudo-scientific.[279] The government's anti-religious campaign was re-intensified,[280] with increased funding given to the League of Militant Atheists.[272] Priests, imams, and Buddhist monks faced persecution.[268] Religious buildings were demolished, most notably Moscow's Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, destroyed in 1931 to make way for the Palace of the Soviets.[281] Religion retained an influence over the population; in the 1937 census, 57% of respondents were willing to admit to being religious.[282]

Throughout the 1920s, Stalin placed a priority on foreign policy.[283] He personally met with a range of Western visitors, including George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells, both of whom were impressed with him.[284] Through the Communist International, Stalin's government exerted a strong influence over Marxist parties elsewhere;[285] he left the running of the organisation to Bukharin before his ousting.[286] At its 6th Congress in July 1928, Stalin informed delegates that the main threat to socialism came from non-Marxist socialists and social democrats, whom he called "social fascists";[287] Stalin recognised that in many countries, these groups were Marxist–Leninists' main rivals for working-class support.[288] This focus on opposing rival leftists concerned Bukharin, who regarded the growth of fascism and the far right across Europe as a greater threat.[286]

In 1929, Stalin's son Yakov unsuccessfully attempted suicide, shooting himself in the chest and narrowly missing his heart; his failure earned the contempt of Stalin, who is reported to have brushed off the attempt by saying "He can't even shoot straight."[289][290] His relationship with Nadezhda was strained amid their arguments and her mental health problems.[291] In November 1932, after a group dinner in the Kremlin in which Stalin flirted with other women, Nadezhda shot herself in the heart.[292] Publicly, the cause of death was given as appendicitis; Stalin also concealed the real cause of death from his children.[293] Stalin's friends noted that he underwent a significant change following her suicide, becoming emotionally harder.[294]

1932–1939: Major crises

Famine of 1932–1933

Within the Soviet Union, civic disgruntlement against Stalin's government was widespread.[295] Social unrest in urban areas led Stalin to ease some economic policies in 1932.[296] In May 1932, he introduced kolkhoz markets where peasants could trade surplus produce.[297] However, penal sanctions became harsher; a decree in August 1932 made the theft of a handful of grain a capital offence.[298] The second five-year plan reduced production quotas from the first, focusing more on improving living conditions[296] through housing and consumer goods.[296] Emphasis on armament production increased after Adolf Hitler became German chancellor in 1933.[299]

The Soviet Union experienced a major famine which peaked in the winter of 1932–1933,[300] with 5–7 million deaths.[301] The worst affected areas were Ukraine (where the famine was called the Holodomor), Southern Russia, Kazakhstan and the North Caucasus.[302] In the case of Ukraine, historians debate whether the famine was intentional, with the purpose of eliminating a potential independence movement;[303] no documents show Stalin explicitly ordered starvation.[304] Poor weather led to bad harvests in 1931 and 1932,[305] compounded by years of declining productivity.[301] Rapid industrialisation policies, neglect of crop rotation, and failure to build reserve grain stocks exacerbated the crisis.[306] Stalin blamed hostile elements and saboteurs among the peasants.[307] The government provided limited food aid to famine-stricken areas, prioritising urban workers;[308] for Stalin, Soviet industrialisation was more valuable than peasant lives.[309] Grain exports declined heavily.[310] Stalin did not acknowledge his policies' role in the famine,[298] which was concealed from foreign observers.[311]

Ideological and foreign affairs

In 1936, Stalin oversaw the adoption of a new constitution with expansive democratic features; it was designed as propaganda, as all power rested in his hands.[312] He declared that "socialism, the first phase of communism, has been achieved".[312] In 1938, the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) was released;[313] commonly known as the "Short Course", it became the central text of Stalinism.[314] Authorised Stalin biographies were also published,[315] though Stalin preferred to be viewed as the embodiment of the Communist Party, rather than have his life story explored.[316]

Seeking better international relations, in 1934 the Soviet Union joined the League of Nations, from which it had previously been excluded.[317] Stalin initiated confidential communications with Hitler in October 1933, shortly after the latter came to power.[318] Stalin admired Hitler, particularly his manoeuvres to remove rivals within the Nazi Party in the Night of the Long Knives.[319] Stalin nevertheless recognised the threat posed by fascism and sought to establish better links with the liberal democracies of Western Europe;[320] in May 1935, the Soviets signed treaties of mutual assistance with France and Czechoslovakia.[321] At the Communist International's 7th Congress in July–August 1935, the Soviet Union encouraged Marxist–Leninists to unite with other leftists as part of a popular front against fascism.[322] In response, Germany, Italy, and Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact.[323]

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936, the Soviets sent military aid to the Republican faction, including 648 aircraft and 407 tanks, along with 3,000 Soviet troops and 42,000 members of the International Brigades.[324] Stalin took a personal involvement in the Spanish situation.[325] Germany and Italy backed the Nationalist faction, which was ultimately victorious in March 1939.[326] With the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in July 1937, the Soviet Union and China signed a non-aggression pact.[327] Stalin aided the Chinese as the KMT and the Communists suspended their civil war and formed his desired United Front against Japan.[328]

Great Purge

Stalin's approach to state repression was often contradictory.[329] In May 1933, he released many convicted of minor offences, ordering the security services not to enact further mass arrests and deportations,[330] and in September 1934, he launched a commission to investigate false imprisonments. That same month, he called for the execution of workers at the Stalin Metallurgical Factory accused of spying for Japan.[329][330] After Sergei Kirov was murdered in December 1934, Stalin became increasingly concerned about assassination threats,[331] and state repression intensified.[332] Stalin issued a decree establishing NKVD troikas which could issue rapid and severe sentences without involving the courts.[333] In 1935, he ordered the NKVD to expel suspected counterrevolutionaries from urban areas;[299] over 11,000 were expelled from Leningrad alone in early 1935.[299]

In 1936, Nikolai Yezhov became head of the NKVD,[334] after which Stalin move to orchestrate the arrest and execution of his remaining opponents in the Communist Party in the Great Purge.[335] The first Moscow Trial in August 1936 saw Kamenev and Zinoviev executed.[336] The second trial took place in January 1937,[337] and the third in March 1938, with Bukharin and Rykov executed.[338] By late 1937, all remnants of collective leadership were gone from the Politburo, which was now effectively under Stalin's control.[339] There were mass expulsions from the party,[340] with Stalin also ordering foreign communist parties to purge anti-Stalinist elements.[341] These purges replaced most of the party's old guard with younger officials loyal to Stalin.[342] Party functionaries readily carried out their commands and sought to ingratiate themselves with Stalin, to avoid becoming victims.[343] Such functionaries often carried out more arrests and executions than their quotas set by government.[344]

Repressions intensified further from December 1936 until November 1938.[346] In May 1937, Stalin ordered the arrest of much of the army's high command, and mass arrests in the military followed.[347] By late 1937, purges extended beyond the party to the wider population.[348] In July 1937, the Politburo ordered a purge of "anti-Soviet elements", targeting anti-Stalin Bolsheviks, former Mensheviks, Socialist Revolutionaries, priests, ex–White Army soldiers, and common criminals.[349] Stalin initiated "national operations", the ethnic cleansing of non-Soviet ethnic groups — among them Poles, Germans, Latvians, Finns, Greeks, Koreans, and Chinese — through internal or external exile.[350] More than 1.6 million people were arrested, 700,000 shot, and an unknown number died under torture.[351] The NKVD also assassinated defectors and opponents abroad;[352] in August 1940, Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico, eliminating Stalin's last major opponent.[353]

Stalin initiated all key decisions during the purge, and personally directed many operations.[354] Historians debate his motives,[351] noting his personal writings from the period were "unusually convoluted and incoherent", filled with claims about enemies encircling him.[355] He feared a domestic fifth column in the event of war with Japan and Germany,[356] particularly after right-wing forces overthrew the leftist Spanish government.[357] The Great Purge ended when Yezhov was replaced by Lavrentiy Beria,[358] a fellow Georgian completely loyal to Stalin.[359] Yezhov himself was arrested in April 1939 and executed in 1940.[360] The purge damaged the Soviet Union's reputation abroad, particularly among leftist sympathisers.[361] As it wound down, Stalin sought to deflect his responsibility,[362] blaming its "excesses" and "violations of law" on Yezhov.[363]

World War II

1939–1941: Pact with Nazi Germany

As a Marxist–Leninist, Stalin considered conflict between competing capitalist powers inevitable; after Nazi Germany annexed Austria and then part of Czechoslovakia in 1938, he recognised a major war was looming.[364] He sought to maintain Soviet neutrality, hoping that a German war against France and the United Kingdom would lead to Soviet dominance in Europe.[365] The Soviets also faced a threat from the east, with Soviet troops clashing with the expansionist Japanese in the latter part of the 1930s, culminating in the Battles of Khalkhin Gol in 1939.[366] Stalin initiated a military build-up, with the Red Army more than doubling in total size between January 1939 and June 1941, although in its haste to expand many of its officers were poorly trained.[367] Between 1940 and 1941 Stalin also purged the military, leaving it with a severe shortage of trained officers when war later broke out.[368]

As Britain and France seemed unwilling to commit to an alliance with the Soviet Union, Stalin saw a better deal with the Germans.[369] On 3 May 1939, Stalin replaced his Western-oriented foreign minister Maxim Litvinov with Vyacheslav Molotov.[370] Germany began negotiations with the Soviets, proposing that Eastern Europe be divided between the two powers.[371] In August 1939, the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Germany, a non-aggression pact negotiated by Molotov and German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop with a secret protocol dividing Eastern Europe.[372] On 1 September, Germany invaded Poland, leading the UK and France to declare war on Germany.[373] On 17 September, the Red Army entered eastern Poland, officially to restore order.[374] On 28 September, Germany and the Soviet Union exchanged some of their conquered territories,[375] and a German–Soviet Frontier Treaty was signed shortly after in Stalin's presence.[376] The two states continued trading, undermining the British blockade of Germany.[377]

The Soviets further demanded parts of eastern Finland, but the Finnish government refused. The Soviets invaded Finland in November 1939, starting the Winter War; despite numerical inferiority, the Finns kept the Red Army at bay.[378] International opinion backed Finland, with the Soviet Union being expelled from the League of Nations.[379] Embarrassed by their inability to defeat the Finns, the Soviets signed an interim peace treaty, in which they received territorial concessions.[380] In June 1940, the Red Army occupied the Baltic states, which were forcibly merged into the Soviet Union in August;[381] they also invaded and annexed Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, parts of Romania.[382] The Soviets sought to forestall dissent in the new territories with mass repressions.[383] A noted instance was the Katyn massacre of April and May 1940, in which around 22,000 members of the Polish armed forces, police, and intelligentsia were executed by the NKVD.[384]

The speed of the German victory over and occupation of France in mid-1940 took Stalin by surprise.[385] He increasingly focused on appeasement with the Germans to delay a conflict with them.[386] After the Tripartite Pact was signed by the Axis Powers of Germany, Japan, and Italy in October 1940, Stalin proposed that the USSR also join the Axis alliance.[387] To demonstrate peaceful intentions, in April 1941 the Soviets signed a neutrality pact with Japan.[388] Stalin, who had been the country's de facto head of government for almost 15 years, concluded that relations with Germany had deteriorated to such an extent that he needed to become de jure head of government as well, and on 6 May, replaced Molotov as Premier of the Soviet Union.[389]

1941–1942: German invasion

In June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union, initiating the war on the Eastern Front.[390] Despite intelligence agencies repeatedly warning him of Germany's intentions, Stalin was taken by surprise.[391] He formed a State Defence Committee, which he headed as Supreme Commander,[392] as well as a military Supreme Command (Stavka),[393] with Georgy Zhukov as its Chief of Staff.[394] The German tactic of blitzkrieg was initially highly effective; the Soviet air force in the western borderlands was destroyed within two days.[395] The German Wehrmacht pushed deep into Soviet territory;[396] soon, Ukraine, Byelorussia, and the Baltic states were under German occupation, and Leningrad was under siege;[397] and Soviet refugees were flooding into Moscow and surrounding cities.[398] By July, Germany's Luftwaffe was bombing Moscow,[397] and by October the Wehrmacht was amassing for a full assault on the capital. Plans were made for the Soviet government to evacuate to Kuibyshev, although Stalin decided to remain in Moscow, believing his flight would damage troop morale.[399] The German advance on Moscow was halted after two months of battle in increasingly harsh weather conditions.[400]

Going against the advice of Zhukov and other generals, Stalin emphasised attack over defence.[401] In June 1941, he ordered a scorched earth policy of destroying infrastructure and food supplies before the Germans could seize them,[402] also commanding the NKVD to kill around 100,000 political prisoners in areas the Wehrmacht approached.[403] He purged the military command; several high-ranking figures were demoted or reassigned and others were arrested and executed.[404] With Order No. 270, Stalin commanded soldiers risking capture to fight to the death, describing the captured as traitors;[405] among those taken as a prisoner of war was Stalin's son Yakov, who died in German custody.[406] Stalin issued Order No. 227 in July 1942, which directed that those retreating unauthorised would be placed in "penal battalions" and used as cannon fodder.[407] Both the German and Soviet armies disregarded the laws of war in the Geneva Conventions;[408] the Soviets heavily publicised Nazi massacres of communists, Jews, and Romani.[409] In April 1942, Stalin sponsored the formation of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC) to garner global Jewish support for the war effort.[410]

The Soviets allied with the UK and U.S.;[411] although the U.S. joined the war against Germany in 1941, little direct American assistance reached the Soviets until late 1942.[408] Responding to the invasion, the Soviets expanded their industry in central Russia, focusing almost entirely on military production.[412] They achieved high levels of productivity, outstripping Germany.[409] During the war, Stalin was more tolerant of the Russian Orthodox Church and allowed it to resume some of its activities.[413] He also permitted a wider range of cultural expression, notably permitting formerly suppressed writers and artists like Anna Akhmatova and Dmitri Shostakovich to disperse their work more widely.[414] "The Internationale" was dropped as the country's national anthem, to be replaced with a more patriotic song.[415] The government increasingly promoted Pan-Slavist sentiment,[416] while encouraging increased criticism of cosmopolitanism, particularly "rootless cosmopolitanism", an approach with particular repercussions for Soviet Jews.[417] The Communist International was dissolved in 1943,[418] and Stalin began encouraging foreign Marxist–Leninist parties to emphasise nationalism over internationalism in order to broaden their domestic appeal.[416]

In April 1942, Stalin overrode Stavka by ordering the Soviets' first serious counter-attack, an attempt to seize German-held Kharkov in eastern Ukraine. This attack proved unsuccessful.[419] That year, Hitler shifted his primary goal from an overall victory on the Eastern Front to the goal of securing the oil fields in the southern Soviet Union crucial to a long-term German war effort.[420] While Red Army generals saw evidence that Hitler would shift efforts south, Stalin considered this to be a flanking move in a renewed effort to take Moscow.[421] In June 1942, the German Army began a major offensive in Southern Russia, threatening Stalingrad; Stalin ordered the Red Army to hold the city at all costs,[422] resulting in the protracted Battle of Stalingrad, which became the bloodiest and fiercest battle of the entire war.[423] In February 1943, the German forces attacking Stalingrad surrendered.[424] The Soviet victory there marked a major turning point in the war;[425] in commemoration, Stalin declared himself Marshal of the Soviet Union in March.[426]

1942–1945: Soviet counter-attack

By November 1942, the Soviets had begun to repulse the German southern campaign and, although there were 2.5 million Soviet casualties in that effort, it permitted the Soviets to take the offensive for most of the rest of the war on the Eastern Front.[427] In summer 1943, Germany attempted an encirclement attack at Kursk, which was successfully repulsed by the Soviets.[428] By the end of the year, the Soviets occupied half of the territory taken by the Germans to that point.[429] Soviet military industrial output also had increased substantially from late 1941 to early 1943 after Stalin had moved factories well to the east of the front, safe from invasion and aerial assault.[430]

In Allied countries, Stalin was increasingly depicted in a positive light over the course of the war.[431] In 1941, the London Philharmonic Orchestra performed a concert to celebrate his birthday,[432] and in 1942, Time magazine named him "Man of the Year".[431] When Stalin learnt that people in Western countries affectionately called him "Uncle Joe" he was initially offended, regarding it as undignified.[433] There remained mutual suspicions between Stalin, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, together known as the "Big Three".[434] Churchill flew to Moscow to visit Stalin in August 1942 and again in October 1944.[435] Stalin scarcely left Moscow during the war,[436] frustrating Roosevelt and Churchill with his reluctance to meet them.[437]

In November 1943, Stalin met with Churchill and Roosevelt in Tehran, a location of Stalin's choosing.[438] There, Stalin and Roosevelt got on well, with both desiring the post-war dismantling of the British Empire.[439] At Tehran, the trio agreed that to prevent Germany rising to military prowess yet again, the German state should be broken up.[440] Roosevelt and Churchill also agreed to Stalin's demand that the German city of Königsberg be declared Soviet territory.[440] Stalin was impatient for the UK and U.S. to open up a Western Front to take the pressure off of the East; they eventually did so in mid-1944.[441] Stalin insisted that, after the war, the Soviet Union should incorporate the portions of Poland it had occupied in 1939, which Churchill opposed.[442] Discussing the fate of the Balkans, later in 1944 Churchill agreed to Stalin's suggestion that after the war, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Yugoslavia would come under the Soviet sphere of influence while Greece would come under that of the Western powers.[443]

In 1944, the Soviet Union made significant advances across Eastern Europe toward Germany,[444] including Operation Bagration, a massive offensive in the Byelorussian SSR against the German Army Group Centre.[445] In 1944, the German armies were pushed out of the Baltic states, which were then re-annexed into the Soviet Union.[446] As the Red Army reconquered the Caucasus and Crimea, various ethnic groups living in the region—the Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingushi, Karachai, Balkars, and Crimean Tatars—were accused of having collaborated with the Germans. Using the idea of collective responsibility as a basis, Stalin's government abolished their autonomous republics and between late 1943 and 1944 deported the majority of their populations to Central Asia and Siberia.[447] Over one million people were deported as a result of the policy, with high rates of mortality.[448]

In February 1945, the three leaders met at the Yalta Conference.[449] Roosevelt and Churchill conceded to Stalin's demand that Germany pay the Soviet Union 20 billion dollars in reparations, and that his country be permitted to annex Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in exchange for entering the war against Japan.[450] An agreement was also made that a post-war Polish government should be a coalition consisting of both communist and conservative elements.[451] Privately, Stalin sought to ensure that Poland would come fully under Soviet influence.[452] The Red Army withheld assistance to Polish resistance fighters battling the Germans in the Warsaw Uprising, with Stalin believing that any victorious Polish militants could interfere with his future aspirations to dominate Poland.[453] Stalin placed great emphasis on capturing Berlin before the Western Allies, believing that this would enable him to bring more of Europe under long-term Soviet control. Churchill, concerned by this, unsuccessfully tried to convince the U.S. that they should pursue the same goal.[454]

1945: Victory

In April 1945, the Red Army seized Berlin, Hitler killed himself, and Germany surrendered in May.[455] Stalin had wanted Hitler captured alive; he had his remains brought to Moscow in order to prevent them becoming a relic for Nazi sympathisers.[456] Many Soviet soldiers engaged in looting, pillaging, and rape, both in Germany and parts of Eastern Europe.[457] Stalin refused to punish the offenders.[454] With Germany defeated, Stalin switched focus to the war with Japan, transferring half a million troops to the Far East.[458] Stalin was pressed by his allies to enter the war and wanted to cement the Soviet Union's strategic position in Asia.[459] On 8 August, in between the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet army invaded Japanese-occupied Manchuria and northern Korea, defeating the Kwantung Army.[460] These events led to the Japanese surrender and the war's end.[461] The U.S. rebuffed Stalin's desire for the Red Army to take a role in the Allied occupation of Japan.[462]

At the Potsdam Conference in July–August 1945, Stalin repeated previous promises that he would refrain from a "Sovietisation" of Eastern Europe.[463] Stalin pushed for reparations from Germany without regard to the base minimum supply for German citizens' survival, which worried Harry Truman and Churchill, who thought that Germany would become a financial burden for the Western powers.[464] Stalin also pushed for "war booty", which would permit the Soviet Union to directly seize property from conquered nations without quantitative or qualitative limitation, and a clause was added permitting this to occur with some limitations.[464] Germany was divided into four zones: Soviet, U.S., British, and French, with Berlin—located in the Soviet area—also divided thusly.[465]

Post-war era

1945–1947: Post-war reconstruction

After the war, Stalin was at the apex of his career.[466] Within the Soviet Union he was widely regarded as the embodiment of victory and patriotism,[467] and his armies controlled Central and Eastern Europe up to the River Elbe.[466] In June 1945, Stalin adopted the title of Generalissimo[468] and stood atop Lenin's Mausoleum to watch a celebratory parade led by Zhukov through Red Square.[469] At a banquet held for army commanders, he described the Russian people as "the outstanding nation" and "leading force" within the Soviet Union, the first time that he had unequivocally endorsed Russians over the other Soviet nationalities.[470] In 1946, the state published Stalin's Collected Works.[471] In 1947, it brought out a second edition of his official biography, which glorified him to a greater extent than its predecessor.[472] He was quoted in Pravda on a daily basis and pictures of him remained pervasive on the walls of workplaces and homes.[473]

Despite his strengthened international position, Stalin was cautious about internal dissent and desire for change among the population.[474] He was also concerned about his returning armies, who had been exposed to a wide range of consumer goods in Germany, much of which they had looted and brought back with them. In this he recalled the 1825 Decembrist Revolt by Russian soldiers returning from having defeated France in the Napoleonic Wars.[475] He ensured that returning Soviet prisoners of war went through "filtration" camps as they arrived in the Soviet Union, in which 2,775,700 were interrogated to determine if they were traitors. About half were then imprisoned in labour camps.[476] In the Baltic states, where there was much opposition to Soviet rule, de-kulakisation and de-clericalisation programmes were initiated, resulting in 142,000 deportations between 1945 and 1949.[446] The Gulag system of forced labour camps was expanded further. By January 1953, three percent of the Soviet population was imprisoned or in internal exile, with 2.8 million in "special settlements" in isolated areas and another 2.5 million in camps, penal colonies, and prisons.[477]

The NKVD were ordered to catalogue the scale of destruction during the war.[478] It was established that 1,710 Soviet towns and 70,000 villages had been destroyed.[479] The NKVD recorded that between 26 and 27 million Soviet citizens had been killed, with millions more being wounded, malnourished, or orphaned.[480] In the war's aftermath, some of Stalin's associates suggested modifications to government policy.[481] Post-war Soviet society was more tolerant than its pre-war phase in various respects. Stalin allowed the Russian Orthodox Church to retain the churches it had opened during the war,[482] and academia and the arts were also allowed greater freedom.[483] Recognising the need for drastic steps to be taken to combat inflation and promote economic recovery, in December 1947 Stalin's government devalued the rouble and abolished the food rationing system.[484] Capital punishment was abolished in 1947 but re-instituted in 1950.[485] Stalin's health deteriorated,[486] and he grew increasingly concerned that senior figures might try to oust him.[487] He demoted Molotov,[488] and increasingly favoured Beria and Malenkov for key positions.[489] In the Leningrad affair, the city's leadership was purged amid accusations of treachery; executions of many of the accused took place in 1950.[490]

In the post-war period there were often food shortages in Soviet cities,[491] and the USSR experienced a major famine from 1946 to 1947.[492] Sparked by a drought and ensuing bad harvest in 1946, it was exacerbated by government policy towards food procurement, including the state's decision to build up stocks and export food rather than distributing it to famine-hit areas.[493] Estimates indicate that between one million and 1.5 million people died from malnutrition or disease as a result.[494] While agricultural production stagnated, Stalin focused on a series of major infrastructure projects, including the construction of hydroelectric plants, canals, and railway lines running to the polar north.[495] Many of these were constructed through prison labour.[495]

1947–1950: Cold War policy

In the aftermath of the war, the British Empire declined, leaving the U.S. and USSR as the dominant world powers.[496] Tensions among these former Allies grew,[467] resulting in the Cold War.[497] Although Stalin publicly described the British and U.S. governments as aggressive, he thought it unlikely that a war with them would be imminent, believing that several decades of peace was likely.[498] He nevertheless secretly intensified Soviet research into nuclear weaponry, intent on creating an atom bomb.[466] Still, Stalin foresaw the undesirability of a nuclear conflict, stating that "atomic weapons can hardly be used without spelling the end of the world."[499] He personally took a keen interest in the development of the weapon.[500] In August 1949, the bomb was successfully tested in the deserts outside Semipalatinsk in Kazakhstan.[501] Stalin also initiated a new military build-up; the Soviet army was expanded from 2.9 million soldiers, as it stood in 1949, to 5.8 million by 1953.[502]

The U.S. began pushing its interests on every continent, acquiring air force bases in Africa and Asia and ensuring pro-U.S. regimes took power across Latin America.[503] It launched the Marshall Plan in June 1947, with which it sought to undermine Soviet hegemony throughout Eastern Europe. The U.S. offered financial assistance to countries on the condition that they opened their markets to trade, aware that the Soviets would never agree.[504] The Allies demanded that Stalin withdraw the Red Army from northern Iran. He initially refused, leading to an international crisis in 1946, but relented one year later.[505] Stalin also tried to maximise Soviet influence on the world stage, unsuccessfully pushing for Libya—recently liberated from Italian occupation—to become a Soviet protectorate.[506][507] He sent Molotov as his representative to San Francisco to take part in negotiations to form the United Nations, insisting that the Soviets have a place on its Security Council.[497] In April 1949, the Western powers established the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), an anti-Soviet military alliance led by the U.S.[508] In the West, Stalin was increasingly portrayed as the "most evil dictator alive" and compared to Hitler.[509]

In 1948, Stalin edited and rewrote sections of Falsifiers of History, published as a series of Pravda articles in February 1948 and then in book form. Written in response to public revelations of the 1939 Soviet alliance with Germany, it focused on blaming the Western powers for the war.[510] He also erroneously claimed that the initial German advance in the early part of the war, during Operation Barbarossa, was not a result of Soviet military weakness, but rather a deliberate Soviet strategic retreat.[511] In 1949, celebrations took place to mark Stalin's 70th birthday (although he actually was turning 71 at the time) at which Stalin attended an event at the Bolshoi Theatre alongside Marxist–Leninist leaders from across Europe and Asia.[512]

Eastern Bloc

After the war, Stalin sought to retain Soviet dominance across Eastern Europe while expanding its influence in Asia.[446] Cautiously regarding the responses from the Western Allies, Stalin avoided immediately installing Communist Party governments in Eastern Europe, instead initially ensuring that Marxist-Leninists were placed in coalition ministries.[507] In contrast to his approach to the Baltic states, he rejected the proposal of merging the new communist states into the Soviet Union, rather recognising them as independent nation-states.[513] He was faced with the problem that there were few Marxists left in Eastern Europe, with most having been killed by the Nazis.[514] He demanded that war reparations be paid by Germany and its Axis allies Hungary, Romania, and the Slovak Republic.[467] Aware that the countries of Eastern Europe had been pushed to socialism through invasion rather than revolution, Stalin called them "people's democracies" instead of "dictatorships of the proletariat".[515]

Churchill observed that an "Iron Curtain" had been drawn across Europe, separating the east from the west.[516] In September 1947, a meeting of East European communist leaders established Cominform to co-ordinate the Communist Parties across Eastern Europe and also in France and Italy.[517] Stalin did not personally attend the meeting, sending Andrei Zhdanov in his place.[465] Various East European communists also visited Stalin in Moscow.[518] There, he offered advice on their ideas; for instance, he cautioned against the Yugoslav idea for a Balkan Federation incorporating Bulgaria and Albania.[518] Stalin had a particularly strained relationship with Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito due to the latter's continued calls for a Balkan federation and for Soviet aid for the communist forces in the ongoing Greek Civil War.[519] In March 1948, Stalin launched an anti-Tito campaign, accusing the Yugoslav communists of adventurism and deviating from Marxist–Leninist doctrine.[520] At the second Cominform conference, held in Bucharest in June 1948, East European communist leaders all denounced Tito's government, accusing them of being fascists and agents of Western capitalism.[521] Stalin ordered several assassination attempts on Tito's life and even contemplated an invasion of Yugoslavia itself.[522]

Stalin suggested that a unified, but demilitarised, German state be established, hoping that it would either come under Soviet influence or remain neutral.[523] When the U.S. and UK opposed this, Stalin sought to force their hand by blockading Berlin in June 1948.[524] He gambled that the Western powers would not risk war, but they airlifted supplies into West Berlin until May 1949, when Stalin relented and ended the blockade.[508] In September 1949 the Western powers transformed their zones into an independent Federal Republic of Germany; in response the Soviets formed theirs into the German Democratic Republic in October.[523] In accordance with earlier agreements, the Western powers expected Poland to become an independent state with free democratic elections.[525] In Poland, the Soviets merged various socialist parties into the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR), and vote rigging was used to ensure that the PZPR secured office.[520] The 1947 Hungarian elections were also rigged by Stalin, with the Hungarian Working People's Party taking control.[520] In Czechoslovakia, where the communists did have a level of popular support, they were elected the largest party in 1946.[526] Monarchy was abolished in Bulgaria and Romania.[527] Across Eastern Europe, the Soviet model was enforced, with a termination of political pluralism, agricultural collectivisation, and investment in heavy industry.[521] It was aimed at establishing economic autarky within the Eastern Bloc.[521]

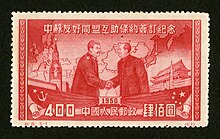

Asia

In October 1949, Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong took power in China and proclaimed the People's Republic of China.[528] Marxist governments now controlled a third of the world's land mass.[529] Privately, Stalin revealed that he had underestimated the Chinese Communists and their ability to win the civil war, instead encouraging them to make another peace with the KMT.[530] In December 1949, Mao visited Stalin. Initially Stalin refused to repeal the Sino-Soviet Treaty of 1945, which significantly benefited the Soviet Union over China, although in January 1950 he relented and agreed to sign a new treaty.[531] Stalin was concerned that Mao might follow Tito's example by pursuing a course independent of Soviet influence, and made it known that if displeased he would withdraw assistance; the Chinese desperately needed said assistance after decades of civil war.[532]

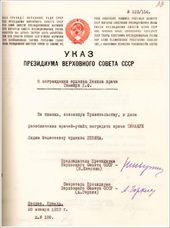

At the end of World War II, the Soviet Union and the United States divided up the Korean Peninsula, formerly a Japanese colonial possession, along the 38th parallel, setting up a communist government in the north and a pro-Western, anti-communist government in the south.[533] North Korean leader Kim Il Sung visited Stalin in March 1949 and again in March 1950; he wanted to invade the south, and although Stalin was initially reluctant to provide support, he eventually agreed by May 1950.[534] The North Korean Army launched the Korean War by invading South Korea in June 1950, making swift gains and capturing Seoul.[535] Both Stalin and Mao believed that a swift victory would ensue.[535] The U.S. went to the UN Security Council—which the Soviets were boycotting over its refusal to recognise Mao's government—and secured international military support for the South Koreans. U.S. led forces pushed the North Koreans back.[536] Stalin wanted to avoid direct Soviet conflict with the U.S., and convinced the Chinese to enter the war to aid the North in October 1950.[537]

The Soviet Union was one of the first nations to extend diplomatic recognition to the newly created state of Israel in 1948, in hopes of obtaining an ally in the Middle East.[538] When the Israeli ambassador Golda Meir arrived in the USSR, Stalin was angered by the Jewish crowds who gathered to greet her.[539] He was further angered by Israel's growing alliance with the U.S.[540] After Stalin fell out with Israel, he launched an anti-Jewish campaign within the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc.[515] In November 1948, he abolished the JAC,[541] and show trials took place for some of its members.[542] The Soviet press engaged in vituperative attacks on Zionism, Jewish culture, and "rootless cosmopolitanism",[543] with growing levels of antisemitism being expressed across Soviet society.[544] Stalin's increasing tolerance of antisemitism may have stemmed from his increasing Russian nationalism or from the recognition that antisemitism had proved a useful tool for Hitler;[545] he may have increasingly viewed the Jewish people as a "counter-revolutionary" nation.[546] There were rumours that Stalin was planning on deporting all Soviet Jews to the Jewish Autonomous Region in Birobidzhan in Siberia.[547]

1950–1953: Final years

In his later years, Stalin was in poor health.[548] He took increasingly long holidays; in 1950 and again in 1951 he spent almost five months on holiday at his Abkhazian dacha.[549] Stalin nevertheless mistrusted his doctors; in January 1952 he had one imprisoned after they suggested that he should retire to improve his health.[548] In September 1952, several Kremlin doctors were arrested for allegedly plotting to kill senior politicians in what came to be known as the doctors' plot; the majority of the accused were Jewish.[550] Stalin ordered that the doctors be tortured to ensure confessions.[551] In November, the Slánský trial took place in Czechoslovakia, in which 13 senior Communist Party figures, 11 of them Jewish, were accused and convicted of being part of a vast Zionist-American conspiracy to subvert the Eastern Bloc.[552] The same month, a much publicised trial of accused Jewish industrial wreckers took place in Ukraine.[553] In 1951, Stalin initiated the Mingrelian affair, a purge of the Georgian Communist Party which resulted in over 11,000 deportations.[554]

From 1946 until his death, Stalin only gave three public speeches, two of which lasted only a few minutes.[555] The amount of written material that he produced also declined.[555] In 1950, Stalin issued the article "Marxism and Problems of Linguistics", which reflected his interest in questions of Russian nationhood.[556] In 1952, Stalin's last book, Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR, was published. It sought to provide a guide to leading the country after his death.[557] In October 1952, he gave an hour and a half speech at the Central Committee plenum.[558] There, he emphasised what he regarded as necessary leadership qualities, and highlighted the weaknesses of potential successors, notably Molotov and Mikoyan.[559] In 1952, he eliminated the Politburo and replaced it with a larger version he named the Presidium.[560]

Death, funeral and aftermath