Aristotle

Aristotle | |

|---|---|

Ἀριστοτέλης | |

Roman copy (in marble) of a Greek bronze bust of Aristotle by Lysippos (c. 330 BC), with modern alabaster mantle | |

| Born | 384 BC |

| Died | 322 BC (aged 61–62) |

| Education | Platonic Academy |

| Notable work | |

| Era | Ancient Greek philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Notable students | Alexander the Great, Theophrastus, Aristoxenus |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | Aristotelianism

Theoretical philosophy Natural philosophy Practical philosophy

|

Aristotle[A] (Attic Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης, romanized: Aristotélēs;[B] 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, and the arts. As the founder of the Peripatetic school of philosophy in the Lyceum in Athens, he began the wider Aristotelian tradition that followed, which set the groundwork for the development of modern science.

Little is known about Aristotle's life. He was born in the city of Stagira in northern Greece during the Classical period. His father, Nicomachus, died when Aristotle was a child, and he was brought up by a guardian. At around eighteen years old, he joined Plato's Academy in Athens and remained there until the age of thirty seven (c. 347 BC). Shortly after Plato died, Aristotle left Athens and, at the request of Philip II of Macedon, tutored his son Alexander the Great beginning in 343 BC. He established a library in the Lyceum, which helped him to produce many of his hundreds of books on papyrus scrolls.

Though Aristotle wrote many treatises and dialogues for publication, only around a third of his original output has survived, none of it intended for publication. Aristotle provided a complex synthesis of the various philosophies existing prior to him. His teachings and methods of inquiry have had a significant impact across the world, and remain a subject of contemporary philosophical discussion.

Aristotle's views profoundly shaped medieval scholarship. The influence of his physical science extended from late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages into the Renaissance, and was not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics were developed. He influenced Judeo-Islamic philosophies during the Middle Ages, as well as Christian theology, especially the Neoplatonism of the Early Church and the scholastic tradition of the Catholic Church.

Aristotle was revered among medieval Muslim scholars as "The First Teacher", and among medieval Christians like Thomas Aquinas as simply "The Philosopher", while the poet Dante called him "the master of those who know". His works contain the earliest known formal study of logic, and were studied by medieval scholars such as Peter Abelard and Jean Buridan. Aristotle's influence on logic continued well into the 19th century. In addition, his ethics, although always influential, gained renewed interest with the modern advent of virtue ethics.

Life

In general, the details of Aristotle's life are not well-established. The biographies written in ancient times are often speculative and historians only agree on a few salient points.[C] Aristotle was born in 384 BC[D] in Stagira, Chalcidice,[2] about 55 km (34 miles) east of modern-day Thessaloniki.[3][4] He was the son of Nicomachus, the personal physician of King Amyntas of Macedon,[5] and Phaestis, a woman with origins from Chalcis, Euboea.[6] Nicomachus was said to have belonged to the medical guild of Asclepiadae and was likely responsible for Aristotle's early interest in biology and medicine.[7] Ancient tradition held that Aristotle's family descended from the legendary physician Asclepius and his son Machaon.[8] Both of Aristotle's parents died when he was still at a young age and Proxenus of Atarneus became his guardian.[9] Although little information about Aristotle's childhood has survived, he probably spent some time in the Macedonian capital, making his first connections with the Macedonian monarchy.[10]

At the age of seventeen or eighteen, Aristotle moved to Athens to continue his education at Plato's Academy.[11] He became distinguished as a researcher and lecturer, earning for himself the nickname "mind of the school" by his tutor Plato.[12] In Athens, he probably experienced the Eleusinian Mysteries as he wrote when describing the sights one viewed at the Mysteries, "to experience is to learn" (παθεĩν μαθεĩν).[13] Aristotle remained in Athens for nearly twenty years before leaving in 348/47 BC after Plato's death.[14] The traditional story about his departure records that he was disappointed with the Academy's direction after control passed to Plato's nephew Speusippus, although it is possible that the anti-Macedonian sentiments in Athens could have also influenced his decision.[15][16] Aristotle left with Xenocrates to Assos in Asia Minor, where he was invited by his former fellow student Hermias of Atarneus; he stayed there for a few years and left around the time of Hermias' death.[E] While at Assos, Aristotle and his colleague Theophrastus did extensive research in botany and marine biology, which they later continued at the near-by island of Lesbos.[17] During this time, Aristotle married Pythias, Hermias's adoptive daughter and niece, and had a daughter whom they also named Pythias.[18]

In 343/42 BC, Aristotle was invited to Pella by Philip II of Macedon in order to become the tutor to his thirteen-year-old son Alexander;[19] a choice perhaps influenced by the relationship of Aristotle's family with the Macedonian dynasty.[20] Aristotle taught Alexander at the private school of Mieza, in the gardens of the Nymphs, the royal estate near Pella.[21] Alexander's education probably included a number of subjects, such as ethics and politics,[22] as well as standard literary texts, like Euripides and Homer.[23] It is likely that during Aristotle's time in the Macedonian court, other prominent nobles, like Ptolemy and Cassander, would have occasionally attended his lectures.[24] Aristotle encouraged Alexander toward eastern conquest, and his own attitude towards Persia was strongly ethnocentric. In one famous example, he counsels Alexander to be "a leader to the Greeks and a despot to the barbarians".[25] Alexander's education under the guardianship of Aristotle likely lasted for only a few years, as at around the age of sixteen he returned to Pella and was appointed regent of Macedon by his father Philip.[26] During this time, Aristotle is said to have gifted Alexander an annotated copy of the Iliad, which reportedly became one of Alexander's most prized possessions.[27] Scholars speculate that two of Aristotle's now lost works, On kingship and On behalf of the Colonies, were composed by the philosopher for the young prince.[28] After Philip II's assassination in 336 BC, Aristotle returned to Athens for the second and final time a year later.[29]

As a metic, Aristotle could not own property in Athens and thus rented a building known as the Lyceum (named after the sacred grove of Apollo Lykeios), in which he established his own school.[30] The building included a gymnasium and a colonnade (peripatos), from which the school acquired the name Peripatetic.[31] Aristotle conducted courses and research at the school for the next twelve years. He often lectured small groups of distinguished students and, along with some of them, such as Theophrastus, Eudemus, and Aristoxenus, Aristotle built a large library which included manuscripts, maps, and museum objects.[32] While in Athens, his wife Pythias died and Aristotle became involved with Herpyllis of Stagira. They had a son whom Aristotle named after his father, Nicomachus.[33] This period in Athens, between 335 and 323 BC, is when Aristotle is believed to have composed many of his philosophical works.[34] He wrote many dialogues, of which only fragments have survived. Those works that have survived are in treatise form and were not, for the most part, intended for widespread publication; they are generally thought to be lecture aids for his students. His most important treatises include Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics, Politics, On the Soul and Poetics. Aristotle studied and made significant contributions to "logic, metaphysics, mathematics, physics, biology, botany, ethics, politics, agriculture, medicine, dance, and theatre."[35]

While Alexander deeply admired Aristotle, near the end of his life, the two men became estranged having diverging opinions over issues, like the optimal administration of city-states, the treatment of conquered populations, such as the Persians, and philosophical questions, like the definition of braveness.[36] A widespread speculation in antiquity suggested that Aristotle played a role in Alexander's death, but the only evidence of this is an unlikely claim made some six years after the death.[37] Following Alexander's death, anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens was rekindled. In 322 BC, Demophilus and Eurymedon the Hierophant reportedly denounced Aristotle for impiety,[38] prompting him to flee to his mother's family estate in Chalcis, Euboea, at which occasion he was said to have stated "I will not allow the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy"[39] – a reference to Athens's trial and execution of Socrates.[15] He died in Chalcis, Euboea[40][41] of natural causes later that same year, having named his student Antipater as his chief executor and leaving a will in which he asked to be buried next to his wife.[42] Aristotle left his works to Theophrastus, his successor as the head of the Lyceum, who in turn passed them down to Neleus of Scepsis in Asia Minor. There, the papers remained hidden for protection until they were purchased by the collector Apellicon. In the meantime, many copies of Aristotle's major works had already begun to circulate and be used in the Lyceum of Athens, Alexandria, and later in Rome.[43]

Theoretical philosophy

Logic

With the Prior Analytics, Aristotle is credited with the earliest study of formal logic,[44] and his conception of it was the dominant form of Western logic until 19th-century advances in mathematical logic.[45] Kant stated in the Critique of Pure Reason that with Aristotle, logic reached its completion.[46]

Organon

Most of Aristotle's work is probably not in its original form, because it was most likely edited by students and later lecturers. The logical works of Aristotle were compiled into a set of six books called the Organon around 40 BC by Andronicus of Rhodes or others among his followers.[49] The books are:

The order of the books (or the teachings from which they are composed) is not certain, but this list was derived from analysis of Aristotle's writings. It goes from the basics, the analysis of simple terms in the Categories, the analysis of propositions and their elementary relations in On Interpretation, to the study of more complex forms, namely, syllogisms (in the Analytics)[50][51] and dialectics (in the Topics and Sophistical Refutations). The first three treatises form the core of the logical theory stricto sensu: the grammar of the language of logic and the correct rules of reasoning. The Rhetoric is not conventionally included, but it states that it relies on the Topics.[52]

| In words | In terms[G] |

In equations[H] |

|---|---|---|

| All men are mortal. All Greeks are men. ∴ All Greeks are mortal. |

M a P S a M S a P |

|

What is today called Aristotelian logic with its types of syllogism (methods of logical argument),[53] Aristotle himself would have labelled "analytics". The term "logic" he reserved to mean dialectics.

Metaphysics

The word "metaphysics" appears to have been coined by the first century AD editor who assembled various small selections of Aristotle's works to create the treatise we know by the name Metaphysics.[55] Aristotle called it "first philosophy", and distinguished it from mathematics and natural science (physics) as the contemplative (theoretikē) philosophy which is "theological" and studies the divine. He wrote in his Metaphysics (1026a16):

If there were no other independent things besides the composite natural ones, the study of nature would be the primary kind of knowledge; but if there is some motionless independent thing, the knowledge of this precedes it and is first philosophy, and it is universal in just this way, because it is first. And it belongs to this sort of philosophy to study being as being, both what it is and what belongs to it just by virtue of being.[56]

Substance

Aristotle examines the concepts of substance (ousia) and essence (to ti ên einai, "the what it was to be") in his Metaphysics (Book VII), and he concludes that a particular substance is a combination of both matter and form, a philosophical theory called hylomorphism. In Book VIII, he distinguishes the matter of the substance as the substratum, or the stuff of which it is composed. For example, the matter of a house is the bricks, stones, timbers, etc., or whatever constitutes the potential house, while the form of the substance is the actual house, namely 'covering for bodies and chattels' or any other differentia that let us define something as a house. The formula that gives the components is the account of the matter, and the formula that gives the differentia is the account of the form.[57][55]

Immanent realism

Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle's philosophy aims at the universal. Aristotle's ontology places the universal (katholou) in particulars (kath' hekaston), things in the world, whereas for Plato the universal is a separately existing form which actual things imitate. For Aristotle, "form" is still what phenomena are based on, but is "instantiated" in a particular substance.[55]

Plato argued that all things have a universal form, which could be either a property or a relation to other things. When one looks at an apple, for example, one sees an apple, and one can also analyse a form of an apple. In this distinction, there is a particular apple and a universal form of an apple. Moreover, one can place an apple next to a book, so that one can speak of both the book and apple as being next to each other. Plato argued that there are some universal forms that are not a part of particular things. For example, it is possible that there is no particular good in existence, but "good" is still a proper universal form. Aristotle disagreed with Plato on this point, arguing that all universals are instantiated at some period of time, and that there are no universals that are unattached to existing things. In addition, Aristotle disagreed with Plato about the location of universals. Where Plato spoke of the forms as existing separately from the things that participate in them, Aristotle maintained that universals exist within each thing on which each universal is predicated. So, according to Aristotle, the form of apple exists within each apple, rather than in the world of the forms.[55][58]

Potentiality and actuality

Concerning the nature of change (kinesis) and its causes, as he outlines in his Physics and On Generation and Corruption (319b–320a), he distinguishes coming-to-be (genesis, also translated as 'generation') from:

- growth and diminution, which is change in quantity;

- locomotion, which is change in space; and

- alteration, which is change in quality.

Coming-to-be is a change where the substrate of the thing that has undergone the change has itself changed. In that particular change he introduces the concept of potentiality (dynamis) and actuality (entelecheia) in association with the matter and the form. Referring to potentiality, this is what a thing is capable of doing or being acted upon if the conditions are right and it is not prevented by something else. For example, the seed of a plant in the soil is potentially (dynamei) a plant, and if it is not prevented by something, it will become a plant. Potentially, beings can either 'act' (poiein) or 'be acted upon' (paschein), which can be either innate or learned. For example, the eyes possess the potentiality of sight (innate – being acted upon), while the capability of playing the flute can be possessed by learning (exercise – acting). Actuality is the fulfilment of the end of the potentiality. Because the end (telos) is the principle of every change, and potentiality exists for the sake of the end, actuality, accordingly, is the end. Referring then to the previous example, it can be said that an actuality is when a plant does one of the activities that plants do.[55]

For that for the sake of which (to hou heneka) a thing is, is its principle, and the becoming is for the sake of the end; and the actuality is the end, and it is for the sake of this that the potentiality is acquired. For animals do not see in order that they may have sight, but they have sight that they may see.[59]

In summary, the matter used to make a house has potentiality to be a house and both the activity of building and the form of the final house are actualities, which is also a final cause or end. Then Aristotle proceeds and concludes that the actuality is prior to potentiality in formula, in time and in substantiality. With this definition of the particular substance (i.e., matter and form), Aristotle tries to solve the problem of the unity of the beings, for example, "what is it that makes a man one"? Since, according to Plato there are two Ideas: animal and biped, how then is man a unity? However, according to Aristotle, the potential being (matter) and the actual one (form) are one and the same.[55][60]

Epistemology

Aristotle's immanent realism means his epistemology is based on the study of things that exist or happen in the world, and rises to knowledge of the universal, whereas for Plato epistemology begins with knowledge of universal Forms (or ideas) and descends to knowledge of particular imitations of these.[52] Aristotle uses induction from examples alongside deduction, whereas Plato relies on deduction from a priori principles.[52]

Natural philosophy

Aristotle's "natural philosophy" spans a wide range of natural phenomena including those now covered by physics, biology and other natural sciences.[61] In Aristotle's terminology, "natural philosophy" is a branch of philosophy examining the phenomena of the natural world, and includes fields that would be regarded today as physics, biology and other natural sciences. Aristotle's work encompassed virtually all facets of intellectual inquiry. Aristotle makes philosophy in the broad sense coextensive with reasoning, which he also would describe as "science". However, his use of the term science carries a different meaning than that covered by the term "scientific method". For Aristotle, "all science (dianoia) is either practical, poetical or theoretical" (Metaphysics 1025b25). His practical science includes ethics and politics; his poetical science means the study of fine arts including poetry; his theoretical science covers physics, mathematics and metaphysics.[61]

Physics

Five elements

In his On Generation and Corruption, Aristotle related each of the four elements proposed earlier by Empedocles, earth, water, air, and fire, to two of the four sensible qualities, hot, cold, wet, and dry. In the Empedoclean scheme, all matter was made of the four elements, in differing proportions. Aristotle's scheme added the heavenly aether, the divine substance of the heavenly spheres, stars and planets.[62]

| Element | Hot/Cold | Wet/Dry | Motion | Modern state of matter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | Cold | Dry | Down | Solid |

| Water | Cold | Wet | Down | Liquid |

| Air | Hot | Wet | Up | Gas |

| Fire | Hot | Dry | Up | Plasma |

| Aether | (divine substance) |

— | Circular (in heavens) |

Vacuum |

Motion

Aristotle describes two kinds of motion: "violent" or "unnatural motion", such as that of a thrown stone, in the Physics (254b10), and "natural motion", such as of a falling object, in On the Heavens (300a20). In violent motion, as soon as the agent stops causing it, the motion stops also: in other words, the natural state of an object is to be at rest,[63][I] since Aristotle does not address friction.[64] With this understanding, it can be observed that, as Aristotle stated, heavy objects (on the ground, say) require more force to make them move; and objects pushed with greater force move faster.[65][J] This would imply the equation[65]

- ,

incorrect in modern physics.[65]

Natural motion depends on the element concerned: the aether naturally moves in a circle around the heavens,[K] while the 4 Empedoclean elements move vertically up (like fire, as is observed) or down (like earth) towards their natural resting places.[66][64][L]

In the Physics (215a25), Aristotle effectively states a quantitative law, that the speed, v, of a falling body is proportional (say, with constant c) to its weight, W, and inversely proportional to the density,[M] ρ, of the fluid in which it is falling:;[66][64]

Aristotle implies that in a vacuum the speed of fall would become infinite, and concludes from this apparent absurdity that a vacuum is not possible.[66][64] Opinions have varied on whether Aristotle intended to state quantitative laws. Henri Carteron held the "extreme view"[64] that Aristotle's concept of force was basically qualitative,[67] but other authors reject this.[64]

Archimedes corrected Aristotle's theory that bodies move towards their natural resting places; metal boats can float if they displace enough water; floating depends in Archimedes' scheme on the mass and volume of the object, not, as Aristotle thought, its elementary composition.[66]

Aristotle's writings on motion remained influential until the Early Modern period. John Philoponus (in Late antiquity) and Galileo (in Early modern period) are said to have shown by experiment that Aristotle's claim that a heavier object falls faster than a lighter object is incorrect.[61] A contrary opinion is given by Carlo Rovelli, who argues that Aristotle's physics of motion is correct within its domain of validity, that of objects in the Earth's gravitational field immersed in a fluid such as air. In this system, heavy bodies in steady fall indeed travel faster than light ones (whether friction is ignored, or not[66]), and they do fall more slowly in a denser medium.[65][N]

Newton's "forced" motion corresponds to Aristotle's "violent" motion with its external agent, but Aristotle's assumption that the agent's effect stops immediately it stops acting (e.g., the ball leaves the thrower's hand) has awkward consequences: he has to suppose that surrounding fluid helps to push the ball along to make it continue to rise even though the hand is no longer acting on it, resulting in the Medieval theory of impetus.[66]

Four causes

Aristotle suggested that the reason for anything coming about can be attributed to four different types of simultaneously active factors. His term aitia is traditionally translated as "cause", but it does not always refer to temporal sequence; it might be better translated as "explanation", but the traditional rendering will be employed here.[69][70]

- Material cause describes the material out of which something is composed. Thus the material cause of a table is wood. It is not about action. It does not mean that one domino knocks over another domino.[69]

- The formal cause is its form, i.e., the arrangement of that matter. It tells one what a thing is, that a thing is determined by the definition, form, pattern, essence, whole, synthesis or archetype. It embraces the account of causes in terms of fundamental principles or general laws, as the whole (i.e., macrostructure) is the cause of its parts, a relationship known as the whole-part causation. Plainly put, the formal cause is the idea in the mind of the sculptor that brings the sculpture into being. A simple example of the formal cause is the mental image or idea that allows an artist, architect, or engineer to create a drawing.[69]

- The efficient cause is "the primary source", or that from which the change under consideration proceeds. It identifies 'what makes of what is made and what causes change of what is changed' and so suggests all sorts of agents, non-living or living, acting as the sources of change or movement or rest. Representing the current understanding of causality as the relation of cause and effect, this covers the modern definitions of "cause" as either the agent or agency or particular events or states of affairs. In the case of two dominoes, when the first is knocked over it causes the second also to fall over.[69] In the case of animals, this agency is a combination of how it develops from the egg, and how its body functions.[71]

- The final cause (telos) is its purpose, the reason why a thing exists or is done, including both purposeful and instrumental actions and activities. The final cause is the purpose or function that something is supposed to serve. This covers modern ideas of motivating causes, such as volition.[69] In the case of living things, it implies adaptation to a particular way of life.[71]

Optics

Aristotle describes experiments in optics using a camera obscura in Problems, book 15. The apparatus consisted of a dark chamber with a small aperture that let light in. With it, he saw that whatever shape he made the hole, the sun's image always remained circular. He also noted that increasing the distance between the aperture and the image surface magnified the image.[72]

Chance and spontaneity

According to Aristotle, spontaneity and chance are causes of some things, distinguishable from other types of cause such as simple necessity. Chance as an incidental cause lies in the realm of accidental things, "from what is spontaneous". There is also more a specific kind of chance, which Aristotle names "luck", that only applies to people's moral choices.[73][74]

Astronomy

In astronomy, Aristotle refuted Democritus's claim that the Milky Way was made up of "those stars which are shaded by the earth from the sun's rays," pointing out partly correctly that if "the size of the sun is greater than that of the earth and the distance of the stars from the earth many times greater than that of the sun, then... the sun shines on all the stars and the earth screens none of them."[75] He also wrote descriptions of comets, including the Great Comet of 371 BC.[76]

Geology and natural sciences

Aristotle was one of the first people to record any geological observations. He stated that geological change was too slow to be observed in one person's lifetime.[77][78] The geologist Charles Lyell noted that Aristotle described such change, including "lakes that had dried up" and "deserts that had become watered by rivers", giving as examples the growth of the Nile delta since the time of Homer, and "the upheaving of one of the Aeolian islands, previous to a volcanic eruption."'[79]

Meteorologica lends its name to the modern study of meteorology, but its modern usage diverges from the content of Aristotle's ancient treatise on meteors. The ancient Greeks did use the term for a range of atmospheric phenomena, but also for earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Aristotle proposed that the cause of earthquakes was a gas or vapor (anathymiaseis) that was trapped inside the earth and trying to escape, following other Greek authors Anaxagoras, Empedocles and Democritus.[80]

Aristotle also made many observations about the hydrologic cycle. For example, he made some of the earliest observations about desalination: he observed early – and correctly – that when seawater is heated, freshwater evaporates and that the oceans are then replenished by the cycle of rainfall and river runoff ("I have proved by experiment that salt water evaporated forms fresh and the vapor does not when it condenses condense into sea water again.")[81]

Biology

Empirical research

Aristotle was the first person to study biology systematically,[82] and biology forms a large part of his writings. He spent two years observing and describing the zoology of Lesbos and the surrounding seas, including in particular the Pyrrha lagoon in the centre of Lesbos.[83][84] His data in History of Animals, Generation of Animals, Movement of Animals, and Parts of Animals are assembled from his own observations,[85] statements given by people with specialized knowledge, such as beekeepers and fishermen, and less accurate accounts provided by travellers from overseas.[86] His apparent emphasis on animals rather than plants is a historical accident: his works on botany have been lost, but two books on plants by his pupil Theophrastus have survived.[87]

Aristotle reports on the sea-life visible from observation on Lesbos and the catches of fishermen. He describes the catfish, electric ray, and frogfish in detail, as well as cephalopods such as the octopus and paper nautilus. His description of the hectocotyl arm of cephalopods, used in sexual reproduction, was widely disbelieved until the 19th century.[88] He gives accurate descriptions of the four-chambered fore-stomachs of ruminants,[89] and of the ovoviviparous embryological development of the hound shark.[90]

He notes that an animal's structure is well matched to function so birds like the heron (which live in marshes with soft mud and live by catching fish) have a long neck, long legs, and a sharp spear-like beak, whereas ducks that swim have short legs and webbed feet.[91] Darwin, too, noted these sorts of differences between similar kinds of animal, but unlike Aristotle used the data to come to the theory of evolution.[92] Aristotle's writings can seem to modern readers close to implying evolution, but while Aristotle was aware that new mutations or hybridizations could occur, he saw these as rare accidents. For Aristotle, accidents, like heat waves in winter, must be considered distinct from natural causes. He was thus critical of Empedocles's materialist theory of a "survival of the fittest" origin of living things and their organs, and ridiculed the idea that accidents could lead to orderly results.[93] To put his views into modern terms, he nowhere says that different species can have a common ancestor, or that one kind can change into another, or that kinds can become extinct.[94]

Scientific style

Aristotle did not do experiments in the modern sense.[95] He used the ancient Greek term pepeiramenoi to mean observations, or at most investigative procedures like dissection.[96] In Generation of Animals, he finds a fertilized hen's egg of a suitable stage and opens it to see the embryo's heart beating inside.[97][98]

Instead, he practiced a different style of science: systematically gathering data, discovering patterns common to whole groups of animals, and inferring possible causal explanations from these.[99][100] This style is common in modern biology when large amounts of data become available in a new field, such as genomics. It does not result in the same certainty as experimental science, but it sets out testable hypotheses and constructs a narrative explanation of what is observed. In this sense, Aristotle's biology is scientific.[99]

From the data he collected and documented, Aristotle inferred quite a number of rules relating the life-history features of the live-bearing tetrapods (terrestrial placental mammals) that he studied. Among these correct predictions are the following. Brood size decreases with (adult) body mass, so that an elephant has fewer young (usually just one) per brood than a mouse. Lifespan increases with gestation period, and also with body mass, so that elephants live longer than mice, have a longer period of gestation, and are heavier. As a final example, fecundity decreases with lifespan, so long-lived kinds like elephants have fewer young in total than short-lived kinds like mice.[101]

Classification of living things

Aristotle distinguished about 500 species of animals,[103][104] arranging these in the History of Animals in a graded scale of perfection, a nonreligious version of the scala naturae, with man at the top. His system had eleven grades of animal, from highest potential to lowest, expressed in their form at birth: the highest gave live birth to hot and wet creatures, the lowest laid cold, dry mineral-like eggs. Animals came above plants, and these in turn were above minerals.[105][106] He grouped what the modern zoologist would call vertebrates as the hotter "animals with blood", and below them the colder invertebrates as "animals without blood". Those with blood were divided into the live-bearing (mammals), and the egg-laying (birds, reptiles, fish). Those without blood were insects, crustacea (non-shelled – cephalopods, and shelled) and the hard-shelled molluscs (bivalves and gastropods). He recognised that animals did not exactly fit into a linear scale, and noted various exceptions, such as that sharks had a placenta like the tetrapods. To a modern biologist, the explanation, not available to Aristotle, is convergent evolution.[107] Philosophers of science have generally concluded that Aristotle was not interested in taxonomy,[108][109] but zoologists who studied this question in the early 21st century think otherwise.[110][111][112] He believed that purposive final causes guided all natural processes; this teleological view justified his observed data as an expression of formal design.[113]

| Group | Examples (given by Aristotle) |

Blood | Legs | Souls (Rational, Sensitive, Vegetative) |

Qualities (Hot–Cold, Wet–Dry) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | Man | with blood | 2 legs | R, S, V | Hot, Wet |

| Live-bearing tetrapods | Cat, hare | with blood | 4 legs | S, V | Hot, Wet |

| Cetaceans | Dolphin, whale | with blood | none | S, V | Hot, Wet |

| Birds | Bee-eater, nightjar | with blood | 2 legs | S, V | Hot, Wet, except Dry eggs |

| Egg-laying tetrapods | Chameleon, crocodile | with blood | 4 legs | S, V | Cold, Wet except scales, eggs |

| Snakes | Water snake, Ottoman viper | with blood | none | S, V | Cold, Wet except scales, eggs |

| Egg-laying fishes | Sea bass, parrotfish | with blood | none | S, V | Cold, Wet, including eggs |

| (Among the egg-laying fishes): placental selachians |

Shark, skate | with blood | none | S, V | Cold, Wet, but placenta like tetrapods |

| Crustaceans | Shrimp, crab | without | many legs | S, V | Cold, Wet except shell |

| Cephalopods | Squid, octopus | without | tentacles | S, V | Cold, Wet |

| Hard-shelled animals | Cockle, trumpet snail | without | none | S, V | Cold, Dry (mineral shell) |

| Larva-bearing insects | Ant, cicada | without | 6 legs | S, V | Cold, Dry |

| Spontaneously generating | Sponges, worms | without | none | S, V | Cold, Wet or Dry, from earth |

| Plants | Fig | without | none | V | Cold, Dry |

| Minerals | Iron | without | none | none | Cold, Dry |

Psychology

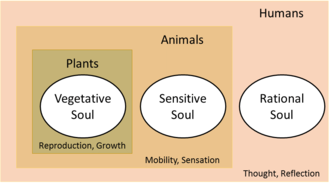

Soul

Aristotle's psychology, given in his treatise On the Soul (peri psychēs), posits three kinds of soul ("psyches"): the vegetative soul, the sensitive soul, and the rational soul. Humans have all three. The vegetative soul is concerned with growth and nourishment. The sensitive soul experiences sensations and movement. The unique part of the human, rational soul is its ability to receive forms of other things and to compare them using the nous (intellect) and logos (reason).[114]

For Aristotle, the soul is the form of a living being. Because all beings are composites of form and matter, the form of living beings is that which endows them with what is specific to living beings, e.g. the ability to initiate movement (or in the case of plants, growth and transformations, which Aristotle considers types of movement).[115] In contrast to earlier philosophers, but in accordance with the Egyptians, he placed the rational soul in the heart, rather than the brain.[116] Notable is Aristotle's division of sensation and thought, which generally differed from the concepts of previous philosophers, with the exception of Alcmaeon.[117]

In On the Soul, Aristotle famously criticizes Plato's theory of the soul and develops his own in response. The first criticism is against Plato's view of the soul in the Timaeus that the soul takes up space and is able to come into physical contact with bodies.[118] 20th-century scholarship overwhelmingly opposed Aristotle's interpretation of Plato and maintained that he had misunderstood him.[119] Today's scholars have tended to re-assess Aristotle's interpretation and been more positive about it.[120] Aristotle's other criticism is that Plato's view of reincarnation entails that it is possible for a soul and its body to be mis-matched; in principle, Aristotle alleges, any soul can go with any body, according to Plato's theory.[121] Aristotle's claim that the soul is the form of a living being eliminates that possibility and thus rules out reincarnation.[122]

Memory

According to Aristotle in On the Soul, memory is the ability to hold a perceived experience in the mind and to distinguish between the internal "appearance" and an occurrence in the past.[123] In other words, a memory is a mental picture (phantasm) that can be recovered. Aristotle believed an impression is left on a semi-fluid bodily organ that undergoes several changes in order to make a memory. A memory occurs when stimuli such as sights or sounds are so complex that the nervous system cannot receive all the impressions at once. These changes are the same as those involved in the operations of sensation, Aristotelian 'common sense', and thinking.[124][125]

Aristotle uses the term 'memory' for the actual retaining of an experience in the impression that can develop from sensation, and for the intellectual anxiety that comes with the impression because it is formed at a particular time and processing specific contents. Memory is of the past, prediction is of the future, and sensation is of the present. Retrieval of impressions cannot be performed suddenly. A transitional channel is needed and located in past experiences, both for previous experience and present experience.[126]

Because Aristotle believes people receive all kinds of sense perceptions and perceive them as impressions, people are continually weaving together new impressions of experiences. To search for these impressions, people search the memory itself.[127] Within the memory, if one experience is offered instead of a specific memory, that person will reject this experience until they find what they are looking for. Recollection occurs when one retrieved experience naturally follows another. If the chain of "images" is needed, one memory will stimulate the next. When people recall experiences, they stimulate certain previous experiences until they reach the one that is needed.[128] Recollection is thus the self-directed activity of retrieving the information stored in a memory impression.[129] Only humans can remember impressions of intellectual activity, such as numbers and words. Animals that have perception of time can retrieve memories of their past observations. Remembering involves only perception of the things remembered and of the time passed.[130]

Aristotle believed the chain of thought, which ends in recollection of certain impressions, was connected systematically in relationships such as similarity, contrast, and contiguity, described in his laws of association. Aristotle believed that past experiences are hidden within the mind. A force operates to awaken the hidden material to bring up the actual experience. According to Aristotle, association is the power innate in a mental state, which operates upon the unexpressed remains of former experiences, allowing them to rise and be recalled.[131][132]

Dreams

Aristotle describes sleep in On Sleep and Wakefulness.[133] Sleep takes place as a result of overuse of the senses[134] or of digestion,[135] so it is vital to the body.[134] While a person is asleep, the critical activities, which include thinking, sensing, recalling and remembering, do not function as they do during wakefulness. Since a person cannot sense during sleep, they cannot have desire, which is the result of sensation. However, the senses are able to work during sleep,[136] albeit differently,[133] unless they are weary.[134]

Dreams do not involve actually sensing a stimulus. In dreams, sensation is still involved, but in an altered manner.[134] Aristotle explains that when a person stares at a moving stimulus such as the waves in a body of water, and then looks away, the next thing they look at appears to have a wavelike motion. When a person perceives a stimulus and the stimulus is no longer the focus of their attention, it leaves an impression.[133] When the body is awake and the senses are functioning properly, a person constantly encounters new stimuli to sense and so the impressions of previously perceived stimuli are ignored.[134] However, during sleep the impressions made throughout the day are noticed as there are no new distracting sensory experiences.[133] So, dreams result from these lasting impressions. Since impressions are all that are left and not the exact stimuli, dreams do not resemble the actual waking experience.[137] During sleep, a person is in an altered state of mind. Aristotle compares a sleeping person to a person who is overtaken by strong feelings toward a stimulus. For example, a person who has a strong infatuation with someone may begin to think they see that person everywhere because they are so overtaken by their feelings. Since a person sleeping is in a suggestible state and unable to make judgements, they become easily deceived by what appears in their dreams, like the infatuated person.[133] This leads the person to believe the dream is real, even when the dreams are absurd in nature.[133] In De Anima iii 3, Aristotle ascribes the ability to create, to store, and to recall images in the absence of perception to the faculty of imagination, phantasia.[115]

One component of Aristotle's theory of dreams disagrees with previously held beliefs. He claimed that dreams are not foretelling and not sent by a divine being. Aristotle reasoned naturalistically that instances in which dreams do resemble future events are simply coincidences.[138] Aristotle claimed that a dream is first established by the fact that the person is asleep when they experience it. If a person had an image appear for a moment after waking up or if they see something in the dark it is not considered a dream because they were awake when it occurred. Secondly, any sensory experience that is perceived while a person is asleep does not qualify as part of a dream. For example, if, while a person is sleeping, a door shuts and in their dream they hear a door is shut, this sensory experience is not part of the dream. Lastly, the images of dreams must be a result of lasting impressions of waking sensory experiences.[137]

Practical philosophy

Aristotle's practical philosophy covers areas such as ethics, politics, economics, and rhetoric.[61]

| Too little | Virtuous mean | Too much |

|---|---|---|

| Humbleness | High-mindedness | Vainglory |

| Lack of purpose | Right ambition | Over-ambition |

| Spiritlessness | Good temper | Irascibility |

| Rudeness | Civility | Obsequiousness |

| Cowardice | Courage | Rashness |

| Insensibility | Self-control | Intemperance |

| Sarcasm | Sincerity | Boastfulness |

| Boorishness | Wit | Buffoonery |

| Shamelessness | Modesty | Shyness |

| Callousness | Just resentment | Spitefulness |

| Pettiness | Generosity | Vulgarity |

| Meanness | Liberality | Wastefulness |

Ethics

Aristotle considered ethics to be a practical rather than theoretical study, i.e., one aimed at becoming good and doing good rather than knowing for its own sake. He wrote several treatises on ethics, most notably including the Nicomachean Ethics.[139]

Aristotle taught that virtue has to do with the proper function (ergon) of a thing. An eye is only a good eye in so much as it can see, because the proper function of an eye is sight. Aristotle reasoned that humans must have a function specific to humans, and that this function must be an activity of the psuchē (soul) in accordance with reason (logos). Aristotle identified such an optimum activity (the virtuous mean, between the accompanying vices of excess or deficiency[35]) of the soul as the aim of all human deliberate action, eudaimonia, generally translated as "happiness" or sometimes "well-being". To have the potential of ever being happy in this way necessarily requires a good character (ēthikē aretē), often translated as moral or ethical virtue or excellence.[140]

Aristotle taught that to achieve a virtuous and potentially happy character requires a first stage of having the fortune to be habituated not deliberately, but by teachers, and experience, leading to a later stage in which one consciously chooses to do the best things. When the best people come to live life this way their practical wisdom (phronesis) and their intellect (nous) can develop with each other towards the highest possible human virtue, the wisdom of an accomplished theoretical or speculative thinker, or in other words, a philosopher.[141]

Politics

In addition to his works on ethics, which address the individual, Aristotle addressed the city in his work titled Politics. Aristotle considered the city to be a natural community. Moreover, he considered the city to be prior in importance to the family, which in turn is prior to the individual, "for the whole must of necessity be prior to the part".[142] He famously stated that "man is by nature a political animal" and argued that humanity's defining factor among others in the animal kingdom is its rationality.[143] Aristotle conceived of politics as being like an organism rather than like a machine, and as a collection of parts none of which can exist without the others. Aristotle's conception of the city is organic, and he is considered one of the first to conceive of the city in this manner.[144]

The common modern understanding of a political community as a modern state is quite different from Aristotle's understanding. Although he was aware of the existence and potential of larger empires, the natural community according to Aristotle was the city (polis) which functions as a political "community" or "partnership" (koinōnia). The aim of the city is not just to avoid injustice or for economic stability, but rather to allow at least some citizens the possibility to live a good life, and to perform beautiful acts: "The political partnership must be regarded, therefore, as being for the sake of noble actions, not for the sake of living together." This is distinguished from modern approaches, beginning with social contract theory, according to which individuals leave the state of nature because of "fear of violent death" or its "inconveniences".[O]

In Protrepticus, the character 'Aristotle' states:[145]

For we all agree that the most excellent man should rule, i.e., the supreme by nature, and that the law rules and alone is authoritative; but the law is a kind of intelligence, i.e. a discourse based on intelligence. And again, what standard do we have, what criterion of good things, that is more precise than the intelligent man? For all that this man will choose, if the choice is based on his knowledge, are good things and their contraries are bad. And since everybody chooses most of all what conforms to their own proper dispositions (a just man choosing to live justly, a man with bravery to live bravely, likewise a self-controlled man to live with self-control), it is clear that the intelligent man will choose most of all to be intelligent; for this is the function of that capacity. Hence it's evident that, according to the most authoritative judgment, intelligence is supreme among goods.[145]

As Plato's disciple Aristotle was rather critical concerning democracy and, following the outline of certain ideas from Plato's Statesman, he developed a coherent theory of integrating various forms of power into a so-called mixed state:

It is ... constitutional to take ... from oligarchy that offices are to be elected, and from democracy that this is not to be on a property-qualification. This then is the mode of the mixture; and the mark of a good mixture of democracy and oligarchy is when it is possible to speak of the same constitution as a democracy and as an oligarchy.

— Aristotle. Politics, Book 4, 1294b.10–18

Economics

Aristotle made substantial contributions to economic thought, especially to thought in the Middle Ages.[146] In Politics, Aristotle addresses the city, property, and trade. His response to criticisms of private property, in Lionel Robbins's view, anticipated later proponents of private property among philosophers and economists, as it related to the overall utility of social arrangements.[146] Aristotle believed that although communal arrangements may seem beneficial to society, and that although private property is often blamed for social strife, such evils in fact come from human nature. In Politics, Aristotle offers one of the earliest accounts of the origin of money.[146] Money came into use because people became dependent on one another, importing what they needed and exporting the surplus. For the sake of convenience, people then agreed to deal in something that is intrinsically useful and easily applicable, such as iron or silver.[147]

Aristotle's discussions on retail and interest was a major influence on economic thought in the Middle Ages. He had a low opinion of retail, believing that contrary to using money to procure things one needs in managing the household, retail trade seeks to make a profit. It thus uses goods as a means to an end, rather than as an end unto itself. He believed that retail trade was in this way unnatural. Similarly, Aristotle considered making a profit through interest unnatural, as it makes a gain out of the money itself, and not from its use.[147]

Aristotle gave a summary of the function of money that was perhaps remarkably precocious for his time. He wrote that because it is impossible to determine the value of every good through a count of the number of other goods it is worth, the necessity arises of a single universal standard of measurement. Money thus allows for the association of different goods and makes them "commensurable".[147] He goes on to state that money is also useful for future exchange, making it a sort of security. That is, "if we do not want a thing now, we shall be able to get it when we do want it".[147]

Rhetoric

| Part of a series on |

| Rhetoric |

|---|

|

Aristotle's Rhetoric proposes that a speaker can use three basic kinds of appeals to persuade his audience: ethos (an appeal to the speaker's character), pathos (an appeal to the audience's emotion), and logos (an appeal to logical reasoning).[148] He also categorizes rhetoric into three genres: epideictic (ceremonial speeches dealing with praise or blame), forensic (judicial speeches over guilt or innocence), and deliberative (speeches calling on an audience to make a decision on an issue).[149] Aristotle also outlines two kinds of rhetorical proofs: enthymeme (proof by syllogism) and paradeigma (proof by example).[150]

Poetics

Aristotle writes in his Poetics that epic poetry, tragedy, comedy, dithyrambic poetry, painting, sculpture, music, and dance are all fundamentally acts of mimesis ("imitation"), each varying in imitation by medium, object, and manner.[151][152] He applies the term mimesis both as a property of a work of art and also as the product of the artist's intention[151] and contends that the audience's realisation of the mimesis is vital to understanding the work itself.[151] Aristotle states that mimesis is a natural instinct of humanity that separates humans from animals[151][153] and that all human artistry "follows the pattern of nature".[151] Because of this, Aristotle believed that each of the mimetic arts possesses what Stephen Halliwell calls "highly structured procedures for the achievement of their purposes."[154] For example, music imitates with the media of rhythm and harmony, whereas dance imitates with rhythm alone, and poetry with language. The forms also differ in their object of imitation. Comedy, for instance, is a dramatic imitation of men worse than average; whereas tragedy imitates men slightly better than average. Lastly, the forms differ in their manner of imitation – through narrative or character, through change or no change, and through drama or no drama.[155]

While it is believed that Aristotle's Poetics originally comprised two books – one on comedy and one on tragedy – only the portion that focuses on tragedy has survived. Aristotle taught that tragedy is composed of six elements: plot-structure, character, style, thought, spectacle, and lyric poetry.[157] The characters in a tragedy are merely a means of driving the story; and the plot, not the characters, is the chief focus of tragedy. Tragedy is the imitation of action arousing pity and fear, and is meant to effect the catharsis of those same emotions. Aristotle concludes Poetics with a discussion on which, if either, is superior: epic or tragic mimesis. He suggests that because tragedy possesses all the attributes of an epic, possibly possesses additional attributes such as spectacle and music, is more unified, and achieves the aim of its mimesis in shorter scope, it can be considered superior to epic.[158] Aristotle was a keen systematic collector of riddles, folklore, and proverbs; he and his school had a special interest in the riddles of the Delphic Oracle and studied the fables of Aesop.[159]

Gender and sexuality

Aristotle asserted that men were superior to women writing "the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject".[160]

On this ground, proponents of feminist metaphysics have accused Aristotle of misogyny[161] and sexism.[162] However, Aristotle gave equal weight to women's happiness as he did to men's, and commented in his Rhetoric that the things that lead to happiness need to be in women as well as men.[P] Aristotle, like other Greek philosophers such Plato and Xenophon, rejected homosexuality, believing that it could lead people to become immoral due to the fact that he believed it went against nature's purpose.[164][165]

Transmission

More than 2300 years after his death, Aristotle remains one of the most influential people who ever lived.[166][167][168] He contributed to almost every field of human knowledge then in existence, and he was the founder of many new fields. According to the philosopher Bryan Magee, "it is doubtful whether any human being has ever known as much as he did".[169]

Among countless other achievements, Aristotle was the founder of formal logic,[170] pioneered the study of zoology, and left every future scientist and philosopher in his debt through his contributions to the scientific method.[40][171][172] Taneli Kukkonen, observes that his achievement in founding two sciences is unmatched, and his reach in influencing "every branch of intellectual enterprise" including Western ethical and political theory, theology, rhetoric, and literary analysis is equally long. As a result, Kukkonen argues, any analysis of reality today "will almost certainly carry Aristotelian overtones ... evidence of an exceptionally forceful mind."[172] Jonathan Barnes wrote that "an account of Aristotle's intellectual afterlife would be little less than a history of European thought".[173]

Aristotle has been called the father of logic, biology, political science, zoology, embryology, natural law, scientific method, rhetoric, psychology, realism, criticism, individualism, teleology, and meteorology.[175]

The scholar Taneli Kukkonen notes that "in the best 20th-century scholarship Aristotle comes alive as a thinker wrestling with the full weight of the Greek philosophical tradition."[172] What follows is an overview of the transmission and influence of his texts and ideas into the modern era.

His successor, Theophrastus

Aristotle's pupil and successor, Theophrastus, wrote the History of Plants, a pioneering work in botany. Some of his technical terms remain in use, such as carpel from carpos, fruit, and pericarp, from pericarpion, seed chamber.[176] Theophrastus was much less concerned with formal causes than Aristotle was, instead pragmatically describing how plants functioned.[177][178]

Later Greek philosophy

The immediate influence of Aristotle's work was felt as the Lyceum grew into the Peripatetic school. Aristotle's students included Aristoxenus, Dicaearchus, Demetrius of Phalerum, Eudemos of Rhodes, Harpalus, Hephaestion, Mnason of Phocis, Nicomachus, and Theophrastus. Aristotle's influence over Alexander the Great is seen in the latter's bringing with him on his expedition a host of zoologists, botanists, and researchers. He had also learned a great deal about Persian customs and traditions from his teacher. Although his respect for Aristotle was diminished as his travels made it clear that much of Aristotle's geography was clearly wrong, when the old philosopher released his works to the public, Alexander complained "Thou hast not done well to publish thy acroamatic doctrines; for in what shall I surpass other men if those doctrines wherein I have been trained are to be all men's common property?"[179]

Hellenistic science

After Theophrastus, the Lyceum failed to produce any original work. Though interest in Aristotle's ideas survived, they were generally taken unquestioningly.[180] It is not until the age of Alexandria under the Ptolemies that advances in biology can be again found.

The first medical teacher at Alexandria, Herophilus of Chalcedon, corrected Aristotle, placing intelligence in the brain, and connected the nervous system to motion and sensation. Herophilus also distinguished between veins and arteries, noting that the latter pulse while the former do not.[181] Though a few ancient atomists such as Lucretius challenged the teleological viewpoint of Aristotelian ideas about life, teleology (and after the rise of Christianity, natural theology) would remain central to biological thought essentially until the 18th and 19th centuries. Ernst Mayr states that there was "nothing of any real consequence in biology after Lucretius and Galen until the Renaissance."[182]

Revival

Following the decline of the Roman Empire, Aristotle's vast philosophical and scientific corpus lay largely dormant in the West. However, his works underwent a remarkable revival in the Abbasid Caliphate.[183] Translated into Arabic alongside other Greek classics, Aristotle's logic, ethics, and natural philosophy ignited the minds of early Islamic scholars.[184]

Through meticulous commentaries and critical engagements, figures like Al-Farabi and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) breathed new life into Aristotle's ideas. They harmonized his logic with Islamic theology, employed his scientific methodologies to explore the natural world, and even reinterpreted his ethics within the framework of Islamic morality. This revival was not mere imitation. Islamic thinkers embraced Aristotle's rigorous methods while simultaneously challenging his conclusions where they diverged from their own religious beliefs.[185]

Byzantine scholars

Greek Christian scribes played a crucial role in the preservation of Aristotle by copying all the extant Greek language manuscripts of the corpus. The first Greek Christians to comment extensively on Aristotle were Philoponus, Elias, and David in the sixth century, and Stephen of Alexandria in the early seventh century.[186] John Philoponus stands out for having attempted a fundamental critique of Aristotle's views on the eternity of the world, movement, and other elements of Aristotelian thought.[187] Philoponus questioned Aristotle's teaching of physics, noting its flaws and introducing the theory of impetus to explain his observations.[188]

After a hiatus of several centuries, formal commentary by Eustratius and Michael of Ephesus reappeared in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, apparently sponsored by Anna Comnena.[189]

Medieval Islamic world

Aristotle was one of the most revered thinkers in early Islamic theology. Most of the still extant works of Aristotle,[191] as well as a number of the original Greek commentaries, were translated into Arabic and studied by Muslim philosophers, scientists and scholars. Averroes, Avicenna and Alpharabius, who wrote on Aristotle in great depth, also influenced Thomas Aquinas and other Western Christian scholastic philosophers. Alkindus greatly admired Aristotle's philosophy,[192] and Averroes spoke of Aristotle as the "exemplar" for all future philosophers.[193] Medieval Muslim scholars regularly described Aristotle as the "First Teacher".[191] The title was later used by Western philosophers (as in the famous poem of Dante) who were influenced by the tradition of Islamic philosophy.[194]

Medieval Europe

With the loss of the study of ancient Greek in the early medieval Latin West, Aristotle was practically unknown there from c. CE 600 to c. 1100 except through the Latin translation of the Organon made by Boethius. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, interest in Aristotle revived and Latin Christians had translations made, both from Arabic translations, such as those by Gerard of Cremona,[195] and from the original Greek, such as those by James of Venice and William of Moerbeke.

After the Scholastic Thomas Aquinas wrote his Summa Theologica, working from Moerbeke's translations and calling Aristotle "The Philosopher",[196] the demand for Aristotle's writings grew, and the Greek manuscripts returned to the West, stimulating a revival of Aristotelianism in Europe that continued into the Renaissance.[197] These thinkers blended Aristotelian philosophy with Christianity, bringing the thought of Ancient Greece into the Middle Ages. Scholars such as Boethius, Peter Abelard, and John Buridan worked on Aristotelian logic.[198]

According to scholar Roger Theodore Lafferty, Dante built up the philosophy of the Comedy with the works of Aristotle as a foundation, just as the scholastics used Aristotle as the basis for their thinking. Dante knew Aristotle directly from Latin translations of his works and indirectly through quotations in the works of Albert Magnus.[199] Dante even acknowledges Aristotle's influence explicitly in the poem, specifically when Virgil justifies the Inferno's structure by citing the Nicomachean Ethics.[200] Dante famously refers to him as "he / Who is acknowledged Master of those who know".[201][202]

Medieval Judaism

Moses Maimonides (considered to be the foremost intellectual figure of medieval Judaism)[203] adopted Aristotelianism from the Islamic scholars and based his Guide for the Perplexed on it and that became the basis of Jewish scholastic philosophy. Maimonides also considered Aristotle to be the greatest philosopher that ever lived, and styled him as the "chief of the philosophers".[204][205][206] Also, in his letter to Samuel ibn Tibbon, Maimonides observes that there is no need for Samuel to study the writings of philosophers who preceded Aristotle because the works of the latter are "sufficient by themselves and [superior] to all that were written before them. His intellect, Aristotle's is the extreme limit of human intellect, apart from him upon whom the divine emanation has flowed forth to such an extent that they reach the level of prophecy, there being no level higher".[207]

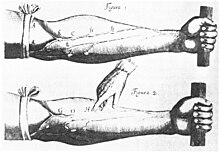

Early Modern science

In the Early Modern period, scientists such as William Harvey in England and Galileo Galilei in Italy reacted against the theories of Aristotle and other classical era thinkers like Galen, establishing new theories based to some degree on observation and experiment. Harvey demonstrated the circulation of the blood, establishing that the heart functioned as a pump rather than being the seat of the soul and the controller of the body's heat, as Aristotle thought.[208] Galileo used more doubtful arguments to displace Aristotle's physics, proposing that bodies all fall at the same speed whatever their weight.[209]

18th and 19th-century science

The English mathematician George Boole fully accepted Aristotle's logic, but decided "to go under, over, and beyond" it with his system of algebraic logic in his 1854 book The Laws of Thought. This gives logic a mathematical foundation with equations, enables it to solve equations as well as check validity, and allows it to handle a wider class of problems by expanding propositions of any number of terms, not just two.[210]

Charles Darwin regarded Aristotle as the most important contributor to the subject of biology. In an 1882 letter he wrote that "Linnaeus and Cuvier have been my two gods, though in very different ways, but they were mere schoolboys to old Aristotle".[211][212] Also, in later editions of the book "On the Origin of Species', Darwin traced evolutionary ideas as far back as Aristotle;[213] the text he cites is a summary by Aristotle of the ideas of the earlier Greek philosopher Empedocles.[214]

Present science

The philosopher Bertrand Russell claims that "almost every serious intellectual advance has had to begin with an attack on some Aristotelian doctrine". Russell calls Aristotle's ethics "repulsive", and labelled his logic "as definitely antiquated as Ptolemaic astronomy". Russell states that these errors make it difficult to do historical justice to Aristotle, until one remembers what an advance he made upon all of his predecessors.[215]

The Dutch historian of science Eduard Jan Dijksterhuis writes that Aristotle and his predecessors showed the difficulty of science by "proceed[ing] so readily to frame a theory of such a general character" on limited evidence from their senses.[216] In 1985, the biologist Peter Medawar could still state in "pure seventeenth century"[217] tones that Aristotle had assembled "a strange and generally speaking rather tiresome farrago of hearsay, imperfect observation, wishful thinking and credulity amounting to downright gullibility".[217][218]

Zoologists have frequently mocked Aristotle for errors and unverified secondhand reports. However, modern observation has confirmed several of his more surprising claims.[219][220][221] Aristotle's work remains largely unknown to modern scientists, though zoologists sometimes mention him as the father of biology[174] or in particular of marine biology.[222] Practising zoologists are unlikely to adhere to Aristotle's chain of being, but its influence is still perceptible in the use of the terms "lower" and "upper" to designate taxa such as groups of plants.[223] The evolutionary biologist Armand Marie Leroi has reconstructed Aristotle's biology,[224] while Niko Tinbergen's four questions, based on Aristotle's four causes, are used to analyse animal behaviour; they examine function, phylogeny, mechanism, and ontogeny.[225][226] The concept of homology began with Aristotle;[227] the evolutionary developmental biologist Lewis I. Held commented that he would be interested in the concept of deep homology.[228] In systematics too, recent studies suggest that Aristotle made important contributions in taxonomy and biological nomenclature.[229][230][231]

Surviving works

Corpus Aristotelicum

The works of Aristotle that have survived from antiquity through medieval manuscript transmission are collected in the Corpus Aristotelicum. These texts, as opposed to Aristotle's lost works, are technical philosophical treatises from within Aristotle's school.[232] Reference to them is made according to the organization of Immanuel Bekker's Royal Prussian Academy edition (Aristotelis Opera edidit Academia Regia Borussica, Berlin, 1831–1870), which in turn is based on ancient classifications of these works.[233]

Loss and preservation

Aristotle wrote his works on papyrus scrolls, the common writing medium of that era.[Q] His writings are divisible into two groups: the "exoteric", intended for the public, and the "esoteric", for use within the Lyceum school.[235][R][236] Aristotle's "lost" works stray considerably in characterization from the surviving Aristotelian corpus. Whereas the lost works appear to have been originally written with a view to subsequent publication, the surviving works mostly resemble lecture notes not intended for publication.[237][235] Cicero's description of Aristotle's literary style as "a river of gold" must have applied to the published works, not the surviving notes.[S] A major question in the history of Aristotle's works is how the exoteric writings were all lost, and how the ones now possessed came to be found.[239] The consensus is that Andronicus of Rhodes collected the esoteric works of Aristotle's school which existed in the form of smaller, separate works, distinguished them from those of Theophrastus and other Peripatetics, edited them, and finally compiled them into the more cohesive, larger works as they are known today.[240][241]

According to Strabo and Plutarch, after Aristotle's death, his library and writings went to Theophrastus (Aristotle's successor as head of the Lycaeum and the Peripatetic school).[242] After the death of Theophrastus, the peripatetic library went to Neleus of Scepsis.[243]: 5

Some time later, the Kingdom of Pergamon began conscripting books for a royal library, and the heirs of Neleus hid their collection in a cellar to prevent it from being seized for that purpose. The library was stored there for about a century and a half, in conditions that were not ideal for document preservation. On the death of Attalus III, which also ended the royal library ambitions, the existence of Aristotelian library was disclosed, and it was purchased by Apellicon and returned to Athens in about 100 BC.[243]: 5–6

Apellicon sought to recover the texts, many of which were seriously degraded at this point due to the conditions in which they were stored. He had them copied out into new manuscripts, and used his best guesswork to fill in the gaps where the originals were unreadable.[243]: 5–6

When Sulla seized Athens in 86 BC, he seized the library and transferred it to Rome. There, Andronicus of Rhodes organized the texts into the first complete edition of Aristotle's works (and works attributed to him).[244] The Aristotelian texts we have today are based on these.[243]: 6–8

Depictions in art

Paintings

Aristotle has been depicted by major artists including Lucas Cranach the Elder,[245] Justus van Gent, Raphael, Paolo Veronese, Jusepe de Ribera,[246] Rembrandt,[247] and Francesco Hayez over the centuries. Among the best-known depictions is Raphael's fresco The School of Athens, in the Vatican's Apostolic Palace, where the figures of Plato and Aristotle are central to the image, at the architectural vanishing point, reflecting their importance.[248] Rembrandt's Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, too, is a celebrated work, showing the knowing philosopher and the blind Homer from an earlier age: as the art critic Jonathan Jones writes, "this painting will remain one of the greatest and most mysterious in the world, ensnaring us in its musty, glowing, pitch-black, terrible knowledge of time."[249][250]

-

Aristotle, mosaic from a Roman villa in Cologne

-

Nuremberg Chronicle anachronistically shows Aristotle in a medieval scholar's clothing. Ink and watercolour on paper, 1493

-

Aristotle by Justus van Gent. Oil on panel, c. 1476

-

Phyllis and Aristotle by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Oil on panel, 1530

-

Aristotle by Paolo Veronese, Biblioteka Marciana. Oil on canvas, 1560s

-

Aristotle by Jusepe de Ribera. Oil on canvas, 1637

-

Aristotle by Johann Jakob Dorner the Elder. Oil on canvas, 1813

-

Aristotle by Francesco Hayez. Oil on canvas, 1811

-

By Charles Laplante "That most enduring of romantic images, Aristotle tutoring the future conqueror Alexander".[172] 1866

Sculptures

-

Roman copy of 1st or 2nd century from original bronze by Lysippos. Louvre Museum

-

Roman copy of 117-138 AD of Greek original. Palermo Regional Archeology Museum

-

Relief of Aristotle and Plato by Luca della Robbia, Florence Cathedral, 1437–1439

-

Stone statue in niche, Gladstone's Library, Hawarden, Wales, 1899

-

Bronze statue, University of Freiburg, Germany, 1915

Eponyms

The Aristotle Mountains in Antarctica are named after Aristotle. He was the first person known to conjecture, in his book Meteorology, the existence of a landmass in the southern high-latitude region, which he called Antarctica.[251] Aristoteles is a crater on the Moon bearing the classical form of Aristotle's name.[252] (6123) Aristoteles, an asteroid in the main asteroid belt is also bearing the classical form of his name.[253]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ /ˈærɪstɒtəl/ ARR-ih-stot-əl[1]

- ^ pronounced [aristotélɛːs]

- ^ See Shields 2012, pp. 3–16. Blits 1999, p. 58 writes that most information about Aristotle's life derives from Diogenes Laertius' Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, which in turn borrows material from earlier, now mostly lost, sources. Düring 1957 covers ancient biographies of Aristotle.

- ^ That these dates (the first half of the Olympiad year 384/383 BC, and in 322 shortly before the death of Demosthenes) are correct was shown by August Boeckh (Kleine Schriften VI 195); for further discussion, see Felix Jacoby on FGrHist 244 F 38. Ingemar Düring, Aristotle in the Ancient Biographical Tradition, Göteborg, 1957, p. 253

- ^ Nussbaum & Osborne 2014, p. 73 write that Hermias died in the year 345 BC; Hazel 2013, p. 37 places Hermias' death in 342 BC, the same year as Aristotle's trip back to Macedon, while Nawotka 2009, p. 40 mentions that Hermias got arrested in 341 BC.

- ^ This type of syllogism, with all three terms in 'a', is known by the traditional (medieval) mnemonic Barbara.[53]

- ^ M is the Middle (here, Men), S is the Subject (Greeks), P is the Predicate (mortal).[53]

- ^ The first equation can be read as 'It is not true that there exists an x such that x is a man and that x is not mortal.'[54]

- ^ Rhett Allain notes that Newton's First Law is "essentially a direct reply to Aristotle, that the natural state is not to change motion.[63]

- ^ Leonard Susskind comments that Aristotle had clearly never gone ice skating or he would have seen that it takes force to stop an object.[65]

- ^ For heavenly bodies like the Sun, Moon, and stars, the observed motions are "to a very good approximation" circular around the Earth's centre, (for example, the apparent rotation of the sky because of the rotation of the Earth, and the rotation of the moon around the Earth) as Aristotle stated.[66]

- ^ Drabkin quotes numerous passages from Physics and On the Heavens (De Caelo) which state Aristotle's laws of motion.[64]

- ^ Drabkin agrees that density is treated quantitatively in this passage, but without a sharp definition of density as weight per unit volume.[64]

- ^ Philoponus and Galileo correctly objected that for the transient phase (still increasing in speed) with heavy objects falling a short distance, the law does not apply: Galileo used balls on a short incline to show this. Rovelli notes that "Two heavy balls with the same shape and different weight do fall at different speeds from an aeroplane, confirming Aristotle's theory, not Galileo's."[66]

- ^ For a different reading of social and economic processes in the Nicomachean Ethics and Politics see Polanyi, Karl (1957) "Aristotle Discovers the Economy" in Primitive, Archaic and Modern Economies: Essays of Karl Polanyi ed. G. Dalton, Boston 1971, 78–115.

- ^ "Where, as among the Lacedaemonians, the state of women is bad, almost half of human life is spoilt."[163]

- ^ "When the Roman dictator Sulla invaded Athens in 86 BC, he brought back to Rome a fantastic prize – Aristotle's library. Books then were papyrus rolls, from 10 to 20 feet long, and since Aristotle's death in 322 BC, worms and damp had done their worst. The rolls needed repairing, and the texts clarifying and copying on to new papyrus (imported from Egypt – Moses' bulrushes). The man in Rome who put Aristotle's library in order was a Greek scholar, Tyrannio."[234]

- ^ Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics 1102a26–27. Aristotle himself never uses the term "esoteric" or "acroamatic". For other passages where Aristotle speaks of exōterikoi logoi, see W.D. Ross, Aristotle's Metaphysics (1953), vol. 2 pp= 408–410. Ross defends an interpretation according to which the phrase, at least in Aristotle's own works, usually refers generally to "discussions not peculiar to the Peripatetic school", rather than to specific works of Aristotle's own.

- ^ "veniet flumen orationis aureum fundens Aristoteles", (Google translation: "Aristotle will come pouring forth a golden stream of eloquence").[238]

- ^ Compare the medieval tale of Phyllis and Alexander above.

Citations

- ^ Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Anagnostopoulos 2013, p. 3; Shields 2012, p. 3; Blits 1999, p. 58; Aristotle (Greek philosopher)

- ^ McLeisch 1999, p. 5; Hazel 2013, p. 36

- ^ Aristoteles-Park in Stagira.

- ^ Ogden 2024, p. 32; Anagnostopoulos 2013, p. 3; Shields 2012, p. 5; Nussbaum & Osborne 2014, p. 73; Hazel 2013, p. 36; Nawotka 2009, p. 40

- ^ Anagnostopoulos 2013, pp. 4; Shields 2012, p. 5; Hazel 2013, pp. 36–37; Reeve & Miller 2015, p. 250

- ^ Anagnostopoulos 2013, p. 4-5; Shields 2012, p. 5; Nussbaum & Osborne 2014, p. 73; Lloyd, Brunschwig & Pellegrin 2000, p. 554

- ^ Lloyd, Brunschwig & Pellegrin 2000, pp. 554–555; Hall 2018

- ^ Hall 2018, p. 14; Anagnostopoulos 2013, p. 4; Shields 2012, p. 5

- ^ Anagnostopoulos 2013, p. 4; Hazel 2013, p. 37; Shields 2012, p. 5

- ^ Nussbaum & Osborne 2014, p. 73; Blits 1999, p. 58

- ^ Hazel 2013, p. 37.

- ^ Evans 2006, p. 18.

- ^ Nussbaum & Osborne 2014, p. 73; Hazel 2013, p. 37

- ^ a b Nussbaum & Osborne 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Aristotle 1984, pp. Introduction.

- ^ Shields 2012, p. 6; Nussbaum & Osborne 2014, p. 73; Hazel 2013, p. 37

- ^ Shields 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Wu 2022, p. 71; Worthington2 2014, pp. 69–70; Nussbaum & Osborne 2014, p. 73; Shields 2012, pp. 6–7; Nawotka 2009, p. 39; Green 1991, p. 54